Upcoming Mentoring Sessions

RMS - Polity - Emergency Provisions

RMS - Geography - Humidity, Clouds & Precipitation

RMS - Economy - Demography, Poverty & Employment

RMS - Modern History - 1813 AD to 1857 AD

RMS - Polity - Union & State Executive

RMS - Modern History - 1932 AD to 1947 AD

RMS - Geography - Basics of Atmosphere

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part III

RMS - Economy - Planning and Mobilisation of Resources

RMS - Modern History - 1919 AD to 1932 AD

RMS - Modern History - 1757 AD to 1813 AD

RMS - Economy - Financial Organisations

RMS - Geography - Major Landforms

RMS - Polity - Constitutional and Statutory Bodies

RMS - Geography - EQ, Faulting and Fracture

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part II

RMS - Economy - Industry, Infrastructure & Investment Models

RMS - Polity - DPSP & FD

RMS - Economy - Indian Agriculture - Part II

RMS - Geography - Rocks & Volcanoes and its landforms

RMS - Geography - Evolution of Oceans & Continents

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part I

RMS - Modern History - 1498 AD to 1757 AD

RMS - Modern History - 1858 AD to 1919 AD

RMS - Geography - Interior of the Earth & Geomorphic Processes

RMS - Geography - Universe and Earth and Basic concepts on Earth

RMS - Economy - Indian Agriculture - Part I

RMS - Economy - Fundamentals of the Indian Economy

RMS - Polity - Union & its territories and Citizenship

RMS - Polity - Constitution & its Salient Features and Preamble

Learning Support Session - ANSWER writing MASTER Session

Learning Support Session - How to Read Newspaper?

Mastering Art of writing Ethics Answers

Mastering Art of Writing Social Issues Answers

Answer Review Session

UPSC CSE 2026 Form Filling Doubt Session

Mentoring Session (2024 - 25) - How to Write an ESSAY?

Social Issues Doubts and Mentoring Session

Ethics & Essay Doubts and Mentoring Session

Geography & Environment Doubts and Mentoring Session

History Doubts and Mentoring Session

Economy & Agriculture Doubts and Mentoring Session

Online Orientation Session

How to Read Newspaper and Make Notes?

Mains Support Programme 2025-(2)

Mains Support Programme 2025- (1)

Polity & International Relations Doubts and Mentoring Session

Mentoring Sessions (2024-25) - How to DO REVISION?

Learning Support Session - How to Start Preparation?

RMS - Geography - World Mapping

Mentoring Session (2024-25) - How to Make Notes?

General Mentoring Session (GMS )

Mentoring Session (2025-26) - How to write an Answer?

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

What is the Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV)?

The highly contagious human metapneumovirus (HMPV) is spreading rapidly across the West Coast of the United States, becoming a major cause of concern for the authorities.

About Human Metapneumovirus (HMPV):

- It is a respiratory virus belonging to the Pneumoviridae family, which also includes the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV).

- It causes symptoms similar to the common cold.

- Transmission:

- The virus is highly contagious. HMPV most likely spreads from an infected person to others through:

- the air by coughing and sneezing

- close personal contact, such as touching or shaking hands

- touching objects or surfaces that have the viruses on them, then touching the mouth, nose, or eyes

- Symptoms:

- Symptoms commonly associated with HMPV include cough, fever, nasal congestion, and shortness of breath.

- In some people, these symptoms may progress to bronchitis or pneumonia.

- The symptoms of HMPV can be similar to symptoms from other viruses that cause upper and lower respiratory infections.

- The majority of the cases are mild, but people with the highest risk of severe illness include young children, older adults, and those who are immunocompromised.

- Treatment:

- There is no vaccine, and there is no specific antiviral to treat HMPV.

- Treatment primarily aims at managing symptoms and preventing complications.

- The virus is highly contagious. HMPV most likely spreads from an infected person to others through:

Science & Tech

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

Key Facts about Raisen Fort

Police in Madhya Pradesh’s Raisen district recently arrested four youths after a video showing cannon firing from the hilltop ASI-protected Raisen Fort and alleged slogans referring to war-prone countries surfaced on social media.

About Raisen Fort:

- Located on a sandstone hill in Raisen town, it is one of the most prominent forts in Madhya Pradesh.

- Built in the 11th century, the Raisen Fort has witnessed the rule of:

- Local Hindu chieftains

- Sultans of Mandu

- Mughals under Akbar (Raisen was a Sarkar headquarters in the Ujjain Subah)

- Nawabs of Bhopal, including Fiaz Mohammad Khan, who occupied the fort around 1760 and was later acknowledged by Emperor Alamgir II as Faujdar of Raisen.

- Features:

- The fort represents medieval Indian hilltop military architecture and offers panoramic views of the surrounding countryside.

- It it one of the largest forts in Central India.

- The fort has a massive stone wall pierced with nine gateways.

- Adorned with a large courtyard and a beautiful pool in the middle, the Raisen Fort has four palaces, namely Badal Mahal, Rohini Mahal, Itradaan Mahal & Hawa Mahal, within its boundaries.

- It also houses a temple dedicated to Lord Shiva and a shrine dedicated to Muslim saint Hazrat Peer Fatehullah Shah Baba, making it a unique blend of Hindu and Islamic heritage.

- The fort also had a well-maintained water management and conservation system with many

- It also abounds in rock shelters with paintings created by the cave dwellers.

Geography

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

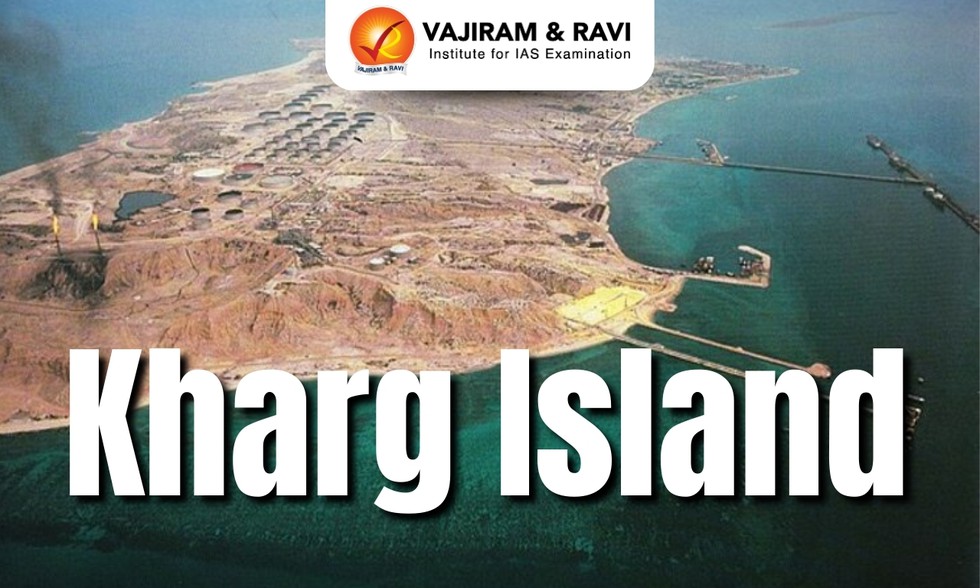

Key Facts about Kharg Island

The United States is considering seizing Iran's Kharg Island to choke off the regime’s oil revenues, a US official has suggested.

About Kharg Island:

- It is a small coral island in Iran in the northern Persian Gulf.

- This island is unique because it is one of the few islands in the Persian Gulf with freshwater, which has collected within the porous limestone.

- The island experiences hot and humid summers, and its highest point is Mount Didehban.

- The discovery of an offshore oil field in the waters around Kharg in the early 1960s stimulated the development of the island as a site for major petroleum and petrochemical installations.

- Connection by pipelines to the underwater oil fields, as well as to the oil fields in Khuzistan province, transformed Kharg into Iran's largest oil-loading terminal by the early 1970s.

- Its strategic significance lies in its proximity to the Strait of Hormuz, a crucial global oil passage.

Source : US could seize strategic oil island

Geography

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

What is Stenothoe lowryi?

For the first time, a rare marine amphipod, a shrimp-like species, named Stenothoe lowryi was found in Indian water at Arjyapalli in Ganjam district by marine science researchers of Berhampur University.

About Stenothoe lowryi:

- It is a rare marine amphipod.

- This shrimp-like crustacean, previously known only from Malaysian shores, was detected for the first time in India during a targeted survey at Aryjapalli Beach in Odisha's Ganjam district.

- It belongs to the family Stenothoidae within the order Amphipoda.

What are Amphipods?

- They are a type of small crustacean.

- They are members of the invertebrate order Amphipoda, inhabiting all parts of the sea, lakes, rivers, sand beaches, caves, and moist (warm) habitats on many tropical islands.

- They are related to crabs, lobsters, and shrimp.

- The name ‘amphipoda’ means “different-footed.”

- This is because they have many different kinds of legs.

- Unlike some other crustaceans, their legs are not all the same.

- They typically have an elongated body with a distinct head, a pereon segments, and a six-segmented pleon (abdomen).

- Most amphipods eat tiny bits of dead plants and animals. Some are also scavengers, eating what they find.

Environment

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

What is the Kheybar Shekan Missile?

Iran’s IRGC claimed it targeted Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu’s office and an air force command centre using Kheybar Shekan missiles recently.

About Kheybar Shekan Missile:

- It is Iran’s latest long-range solid-fuel ballistic missile.

- The name means “breaker of Khayber” in Arabic, a reference to the Battle of Khayber in Arab history.

- It is the fourth generation of the Khorramshahr missile family.

- Features:

- It has a range of 1,450 kilometers.

- It is powered by a locally developed 'Arond' engine integrated within its fuel tank to minimise length and enhance camouflage.

- It uses solid fuel. This allows for faster launch preparation, easier storage, and better concealment, key advantages in modern missile warfare.

- Its aerodynamic design reduces air drag, helping it evade radar detection.

Science & Tech

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

White Phosphorus

Recently, the Human Rights Watch accused Israel of "unlawfully" using white phosphorus over residential parts of a southern Lebanese town.

About White Phosphorus:

- White (sometimes called yellow) phosphorus is a white to yellow waxy solid with a garlic like odour.

- Properties: It ignites spontaneously in air at temperatures above 30 °C and continues to burn until it is fully oxidized or until deprived of oxygen.

- Applications:

- It is often used by militaries to illuminate battlefields, to generate a smokescreen and as an incendiary.

- It is used for military purposes in grenades and artillery shells to produce illumination, to generate a smokescreen and as an incendiary.

- Its major industrial uses are in the production of phosphoric acid, phosphates and other compounds.

- Phosphates are used to manufacture a range of products including fertilizers and detergents. Phosphorus has been used as a rodenticide and in fireworks.

- Impact of White phosphorus on Humans:

- It is harmful to humans by all routes of exposure.

- The smoke from burning phosphorus is also harmful to the eyes and respiratory tract due to the presence of phosphoric acids and phosphine.

- It can cause deep and severe burns, penetrating even through bone.

Science & Tech

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

Narcotics Control Bureau

Recently, the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) has dismantled a pan-India drug distribution network operating under the name Team Kalki.

About Narcotics Control Bureau:

- It is the nodal drug law enforcement and intelligence agency under the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

- It was constituted under the provisions of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 (NDPS Act).

- Functions of Narcotics Control Bureau:

- Coordination among various Central and State Agencies engaged in drug law enforcement;

- Assisting States in enhancing their drug law enforcement effort;

- Collection and dissemination of intelligence;

- Analysis of seizure data, study of trends and modus operandi;

- Preparation of National Drug Enforcement Statistics;

- Liaison with International agencies such as UNDCP, INCB, INTERPOL, Customs Cooperation Council, RILO etc;

- National contact point for intelligence and investigations

- It also functions as an enforcement agency through its zonal offices.

- The zonal offices collect and analyse data related to seizures of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances, study trends, modus operandi, collect and disseminate intelligence, and work in close cooperation with the Customs, State Police, and other law enforcement agencies.

- Headquarters: New Delhi

Polity & Governance

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

ASMITA Initiative

Recently, the Minister of State for Youth Affairs & Sports launch the nationwide athletics league at 250 locations across the subcontinent under the ASMITA (Achieving Sports Milestone by Inspiring Women Through Action) programme.

About ASMITA Initiative:

- It was started in 2021.

- It is part of Khelo India’s gender-neutral mission to promote sports among women through leagues and competitions.

- ASMITA leagues not only aim to increase the participation of women in sports but also to utilize the leagues as a platform for the identification of new talent across the length and breadth of India.

- It is an affirmative action in sports for increasing women’s participation.

- Objective: Inclusive and grassroots-driven sports development.

- The Khelo India ASMITA league is a core component of the ‘Khelo Bharat Niti,’ promoting sports for nation-building and women’s empowerment.

- The Sports Authority of India (SAI) supports National Sports Federations in conducting Khelo India women’s leagues across multiple age groups at both zonal and national levels.

- Nodal Ministry: Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports.

Key Facts about Khelo India:

- It is a flagship Central Sector Scheme of the Ministry of Youth Affairs & Sports, Government of India.

- It is aimed at promoting mass participation and sporting excellence.

- Khelo India Games have been declared an ‘Event of National Importance’ in 2020 under the Sports Broadcasting Signals Act, 2007.

Polity & Governance

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

BharatNet Project

Recently, the government said that through BharatNet project India expanded its optical fibre networks, 5G services and digital public infrastructure to more than 2.15 lakh Gram Panchayats.

About BharatNet Project:

- It is project of the Government of India aimed at providing broadband connectivity to all Gram Panchayats (GPs) in the country.

- Objective: The primary objective is to provide unrestricted access to broadband connectivity to all the telecom service providers.

- This enables access providers like mobile operators, Internet Service Providers (ISPs), Cable TV operators, and content providers to launch various services such as e-health, e-education, and e-governance in rural and remote India.

- Phases of BharatNet Project:

- Phase I: Focused on laying optical fibre cables to connect 1 lakh Gram Panchayats by utilising existing infrastructure. This phase was completed in 2017.

- Phase II(ongoing): Expanded coverage to an additional 1.5 lakh Gram Panchayats using optical fibre, radio, and satellite technologies.

- Phase III (ongoing): Aims at future-proofing the network by integrating 5G technologies, increasing bandwidth capacity, and ensuring robust last-mile connectivity.

- Funding: It is primarily funded through the Digital Bharat Nidhi (DBN), which is a fund that replaced the Universal Service Obligation Fund (USOF).

- Implementation: It is being executed by a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) namely Bharat Broadband Network Limited (BBNL).

Science & Tech

Current Affairs

March 9, 2026

Proba-3 Mission

Recently, the European Space Agency (Esa) has lost contact with one of the two spacecraft powering its Proba-3 mission.

About Proba-3 Mission:

- It is the European Space Agency’s (ESA) first mission dedicated to precision formation flying.

- It is the innovative mission which will demonstrate precision formation flying between two satellites to create an artificial eclipse, revealing new views of the Sun’s faint corona.

- Objective: To create an artificial eclipse by precisely coordinating two independent satellites. This capability will enable scientists to observe the Sun’s corona, a region typically obscured by the intense brightness of the Sun.

- It consists of two small satellites: a Coronagraph spacecraft and a solar-disc-shaped Occulter spacecraft.

- Working

- By flying in tight formation about 150 metres apart, the Occulter will precisely cast its shadow onto the Coronagraph’s telescope, blocking the Sun’s direct light.

- This will allow the Coronagraph to image the faint solar corona in visible, ultraviolet and polarised light for many hours at a time.

- It will provide new insights into the origins of coronal mass ejections (CMEs) — eruptions of solar material that can disrupt satellites and power grids on Earth.

- The mission will also measure total solar irradiance, tracking changes in the Sun’s energy output that may influence Earth’s climate.

Science & Tech