Upcoming Mentoring Sessions

RMS - Polity - Emergency Provisions

RMS - Geography - Humidity, Clouds & Precipitation

RMS - Economy - Demography, Poverty & Employment

RMS - Modern History - 1813 AD to 1857 AD

RMS - Polity - Union & State Executive

RMS - Modern History - 1932 AD to 1947 AD

RMS - Geography - Basics of Atmosphere

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part III

RMS - Economy - Planning and Mobilisation of Resources

RMS - Modern History - 1919 AD to 1932 AD

RMS - Modern History - 1757 AD to 1813 AD

RMS - Economy - Financial Organisations

RMS - Geography - Major Landforms

RMS - Polity - Constitutional and Statutory Bodies

RMS - Geography - EQ, Faulting and Fracture

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part II

RMS - Economy - Industry, Infrastructure & Investment Models

RMS - Polity - DPSP & FD

RMS - Economy - Indian Agriculture - Part II

RMS - Geography - Rocks & Volcanoes and its landforms

RMS - Geography - Evolution of Oceans & Continents

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part I

RMS - Modern History - 1498 AD to 1757 AD

RMS - Modern History - 1858 AD to 1919 AD

RMS - Geography - Interior of the Earth & Geomorphic Processes

RMS - Geography - Universe and Earth and Basic concepts on Earth

RMS - Economy - Indian Agriculture - Part I

RMS - Economy - Fundamentals of the Indian Economy

RMS - Polity - Union & its territories and Citizenship

RMS - Polity - Constitution & its Salient Features and Preamble

Learning Support Session - ANSWER writing MASTER Session

Learning Support Session - How to Read Newspaper?

Mastering Art of writing Ethics Answers

Mastering Art of Writing Social Issues Answers

Answer Review Session

UPSC CSE 2026 Form Filling Doubt Session

Mentoring Session (2024 - 25) - How to Write an ESSAY?

Social Issues Doubts and Mentoring Session

Ethics & Essay Doubts and Mentoring Session

Geography & Environment Doubts and Mentoring Session

History Doubts and Mentoring Session

Economy & Agriculture Doubts and Mentoring Session

Online Orientation Session

How to Read Newspaper and Make Notes?

Mains Support Programme 2025-(2)

Mains Support Programme 2025- (1)

Polity & International Relations Doubts and Mentoring Session

Mentoring Sessions (2024-25) - How to DO REVISION?

Learning Support Session - How to Start Preparation?

RMS - Geography - World Mapping

Mentoring Session (2024-25) - How to Make Notes?

General Mentoring Session (GMS )

Mentoring Session (2025-26) - How to write an Answer?

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

Key Facts about Deepor Beel

Illegal earth cutting from a wetland connected to Deepor Beel is continuing unabated in the Satmile area of Guwahati, despite prohibitory orders from the district administration and restrictions imposed by the Gauhati High Court.

About Deepor Beel:

- It is a permanent freshwater lake in in Assam.

- It lies in a former channel of the Brahmaputra River.

- Beel is an Assamese local word which means ‘lake’, and the name Deepor Beel means the ‘lake of elephants’.

- It is considered one of the biggest lakes of the Brahmaputra Valley of Lower Assam.

- It is surrounded by steep highlands on the northern and southern sides, and its main sources of water are the Kalmani and Basistha Rivers.

- It is the only major stormwater storage basin for the city of Guwahati.

- The lake’s outflow is the Khandajan rivulet, which joins the Brahmaputra.

- It is recognised as a Ramsar Site and as an Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA). It is the only Ramsar site in Assam.

- This lake is a staging site on migratory flyways, and some of the largest concentrations of aquatic birds in Assam can be seen, especially in winter.

- Some globally threatened birds are supported, including Spot-billed Pelican, Lesser Greater Adjutant Stork, and Baer’s Pochard.

- The Rani and Garbhanga hills, the habitat of the Asiatic elephants on the southern side of the beel, are part of this ecosystem.

Geography

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

Deendayal Port

The Deendayal Port in Gujarat's Kandla is gearing up to handle a whopping 22 vessels over a 72-hour period over the weekend

About Deendayal Port:

- Deendayal Port (previously called Kandla Port) is the second largest seaport of India, situated in the Kachchh District of Gujarat.

- It is situated in the creek of Kandla.

- It is a protected natural harbor.

- It is recognized as one of the major ports in India.

- It was constructed in the 1950s as the chief seaport serving western India after the partition of India from Pakistan left the port of Karachi in Pakistan.

- The port is specialized in handling bulk import and export cargo, including liquid cargo.

- It remains India’s biggest state-owned cargo handler by volume, but it has steadily lost market share to privately owned Mundra Port (India’s largest private port).

Geography

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

Key Facts about Musi River

Several historic landmarks have been identified as part of the 55-km Musi river rejuvenation project, with authorities exploring ways to link them through heritage tourism and cultural initiatives along the river corridor.

About Musi River:

- The Musi River, also known as the Muchukunda or Musunuru River, is a major tributary of the Krishna River in the Deccan Plateau, flowing through Telangana.

- The river gained prominence in the late 16th century when Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the founder of Hyderabad, established the city along its banks.

- Course:

- It originates from Anantagiri Hills near Vikarabad District.

- The river is formed by the merging of two small rivulets: Esi and Musa.

- After originating, the Musi River flows in an eastward direction, cutting through the heart of Hyderabad city, where it historically divided the Old City from the New City.

- The river then continues its journey through the southern Telangana plains.

- It ultimately joins the Krishna River near Wazirabad in Nalgonda district.

- Dams: Himayat Sagar and Osman Sagar are the two dams that are constructed over the river.

- Hussain Sagar Lake was built on a tributary of the River Musi.

- Several historic bridges and mosques line its banks, reflecting Qutb Shahi and Nizam-era architecture.

- The Musi River has diversion weirs for irrigation, locally known as kathwas.

- Now due to random urbanization and lack of planning the river has become a holder of all the unprocessed domestic and industrial waste drained out of Hyderabad.

Geography

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

What is Herpes simplex virus (HSV)?

About 92 inmates of Jalpaiguri Central Correctional Home (JCCH) in West Bengal were infected with the Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) between August 20, 2025, and March 9 this year, with seven of the infected inmates losing their lives.

About Herpes simplex virus (HSV):

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV), known as herpes, is a common infection that can cause painful blisters or ulcers.

- There are two types of HSV:

- HSV-1: This type primarily causes oral herpes, characterized by cold sores or fever blisters that appear around mouth or on face.

- HSV-2: This primarily causes genital herpes.

- Transmission:

- HSV is highly contagious. It is spread by skin-to-skin contact with someone who carries the virus.

- Once infected, a person will have the HSV for the rest of their life.

- HSV can periodically reactivate, causing symptoms.

- Symptoms:

- Most people with herpes have no symptoms or only mild symptoms.

- Many people aren’t aware they have the infection and can pass along the virus to others without knowing.

- Others might experience occasional episodes of small, fluid-filled blisters or sores.

- These sores and blisters are typically painful. Blisters may break open, ooze, and then crust over.

- New infections may cause fever, body aches, and swollen lymph nodes.

- In rare cases, infection with HSV-1 or HSV-2 can lead to meningitis (inflammation of the covering of the brain and spinal cord) or encephalitis (inflammation of the brain).

- Treatment:

- It is treatable but not curable.

- Antivirals and home remedies can help ease the severity of symptoms. Antiviral medication may also lead to fewer herpes episodes.

Science & Tech

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

What is Osbeckia zubeengargiana?

Researchers from Gauhati University recently discovered a new plant species named Osbeckia zubeengargiana in Assam.

About Osbeckia zubeengargiana:

- It is a new plant species.

- It was discovered in the grasslands of Manas National Park in Baksa District, Assam.

- It has been named after celebrated Assamese singer Zubeen Garg, marking a rare tribute from the world of botany to a cultural icon of the region.

- The plant belongs to the Melastomataceae family, a group known for its diverse flowering shrubs found across tropical and subtropical regions.

- It is a perennial erect shrub.

- The plant is characterised by its delicate purple to pinkish four-petalled (tetramerous) flowers.

- The shrub thrives in moist soil conditions and blooms seasonally, adding to the floral diversity of the grassland ecosystem.

- The plant typically flowers and bears fruit between mid-September and January.

Environment

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

Key Facts about Tanzania

Recently, India has dispatched a consignment of essential life-saving medicines to Tanzania as humanitarian assistance.

About Tanzania:

- Location: It is an East African country situated just south of the Equator.

- Bordering Countries: It shares borders with eight countries: Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south.

- Maritime Border: The eastern border of Tanzania meets the Indian Ocean.

- Capital: Dar es Salaam (administrative captial), Dodoma (legislative capital).

- Geographical Features of Tanzania:

- Climate type: Tropical, with a long dry season and two rainy seasons.

- Major lakes: Lake Victoria (the world’s second-largest freshwater lake, shared with Uganda and Kenya) in the north, Lake Tanganyika in the west, and Lake Nyasa in the southwest.

- Highest Peak: Mount Kilimanjaro

- Major rivers: Great Ruaha, Rufiji, and Kagera rivers.

- Islands: It includes Zanzibar, Pemba, and Mafia, all located off the eastern coast in the Indian Ocean.

Geography

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

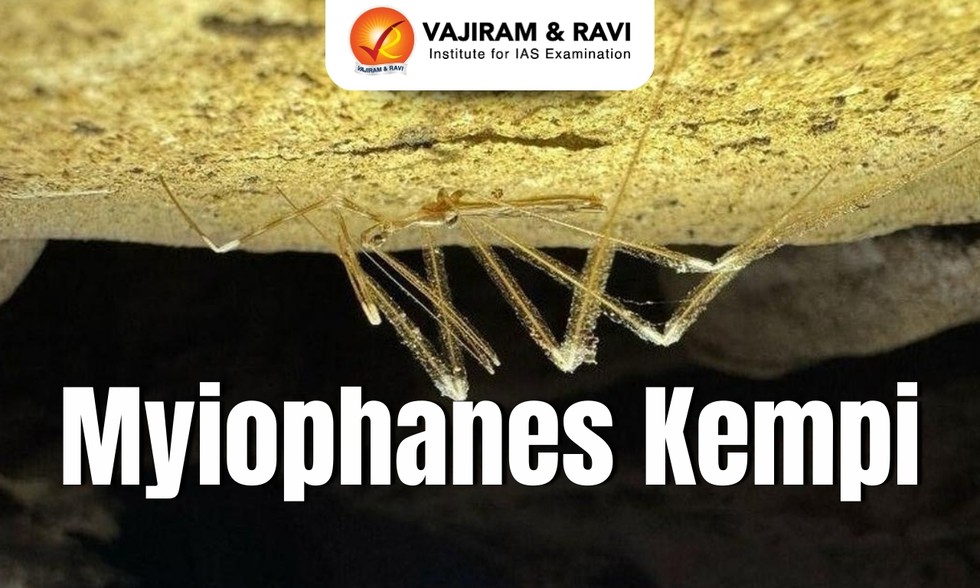

Myiophanes kempi

Recently, researchers rediscovered Myiophanes kempi in limestone caves in the Andaman Islands after almost 100 years gap.

About Myiophanes kempi:

- It is a slender-bodied assassin bug belongs to the sub family of Reduviidae.

- It was first described by British entomologist Willian Edward China in 1924.

- It was previously described from Siju Cave in Meghalaya a century ago.

- Characteristics of Myiophanes kempi:

- It is a specialised predator of the subterranean ecosystem and lives in its complete lifecycle in the darkness.

- It uses the long raptorial forelegs for snatching prey -- small arthropods of the dark cave environment.

Key facts about Siju Cave

- Location: It is one of the longest limestone cave systems in the world situated in Garo Hills in the state of

- It also known as Dobakkol or Bat Cave, is one of India's longest limestone caves.

- It is located near the Simsang River.

- It is famous for its stunning rock formations and underground streams.

Environment

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

Silverpit Crater

New research has confirmed that the Silverpit Crater was formed by a massive asteroid impact millions of years ago.

About Silverpit Crater:

- Location: It lies in the North Sea.

- Formation: It was formed by a high-velocity space rock striking the seabed roughly 43 to 46 million years ago.

- Scientific Evidence: Researchers identified “shocked" quartz and feldspar crystals in rock samples from a nearby oil well that only form under the extreme shock pressures of a high-velocity space impact.

- Features of Silverpit Crater:

- It measures roughly three kilometres wide and is surrounded by a ring of circular faults.

- It is a rare and exceptionally well-preserved hypervelocity impact crater.

- Its round shape and central peak resembled classic impact craters.

Science & Tech

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

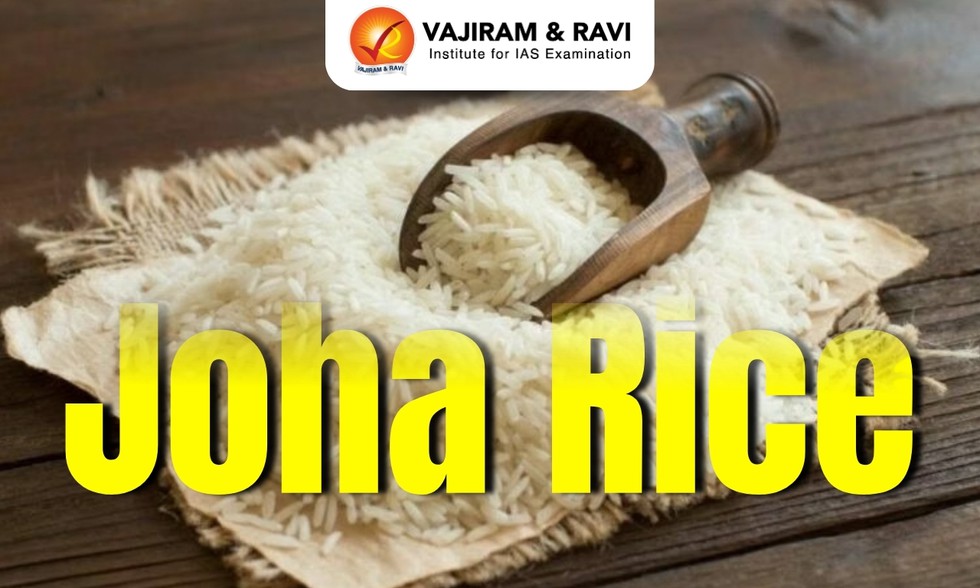

Joha Rice

Recently, India has facilitated the export of 25 metric tonnes of Assam’s GI-tagged Joha Rice to the United Kingdom and Italy.

About Joha Rice:

- It is an indigenous rice of Assam.

- It is an indigenous aromatic rice variety known for its distinct fragrance, fine grain texture and rich taste.

- It is grown in Sali/ Kharif season.

- Major Joha varieties included in this are Kola Joha, Keteki Joha, Bokul Joha and Kunkuni Joha.

- This rice is also rich in several antioxidants, flavonoids, and phenolics.

- It has got Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2017.

- This rice variety has two unsaturated fatty acids viz., linoleic acid (omega-6) and linolenic (omega-3) acid.

- These essential fatty acids (which humans cannot produce) can help maintain various physiological conditions.

What is Geographical Indication Tag?

- It is a sign used on products that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that origin.

- This is typically used for agricultural products, foodstuffs, wine and spirit drinks, handicrafts and industrial products.

- The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999seeks to provide for the registration and better protection of geographical indications relating to goods in India.

- This GI tag is valid for 10 years following which it can be renewed.

Environment

Current Affairs

March 14, 2026

Alprazolam

Recently, the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI) has busted a clandestine facility engaged in the production of Alprazolam in Andhra Pradesh.

About Alprazolam

- It is a psychotropic substance under the Narcotics, Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act 1985.

- This drug falls under the benzodiazepines class of drugs, and is a tranquillizing agent used in the treatment of anxiety disorders.

- Benzodiazepines belong to the group of medicines called central nervous system (CNS) depressants, which are medicines that slow down the nervous system.

- Alprazolam enhances the activity of a neurotransmitter in the brain called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

- Used for: It is used to treat anxiety disorders, panic disorders, and anxiety caused by depression.

Key Facts about Directorate of Revenue Intelligence

- It was constituted in 1957 as the apex anti-smuggling intelligence and investigation agency.

- Functions: It is tasked with detecting and curbing smuggling of contraband, including drug trafficking and illicit international trade in wildlife and environmentally sensitive items, as well as combating commercial frauds related to international trade and evasion of customs duty.

- Nodal Ministry: It works under the Central Board of Indirect Taxes & Customs (CBIC), Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

Science & Tech