Upcoming Mentoring Sessions

RMS - Polity - Emergency Provisions

RMS - Geography - Humidity, Clouds & Precipitation

RMS - Economy - Demography, Poverty & Employment

RMS - Modern History - 1813 AD to 1857 AD

RMS - Polity - Union & State Executive

RMS - Modern History - 1932 AD to 1947 AD

RMS - Geography - Basics of Atmosphere

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part III

RMS - Economy - Planning and Mobilisation of Resources

RMS - Modern History - 1919 AD to 1932 AD

RMS - Modern History - 1757 AD to 1813 AD

RMS - Economy - Financial Organisations

RMS - Geography - Major Landforms

RMS - Polity - Constitutional and Statutory Bodies

RMS - Geography - EQ, Faulting and Fracture

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part II

RMS - Economy - Industry, Infrastructure & Investment Models

RMS - Polity - DPSP & FD

RMS - Economy - Indian Agriculture - Part II

RMS - Geography - Rocks & Volcanoes and its landforms

RMS - Geography - Evolution of Oceans & Continents

RMS - Polity - Fundamental Rights - Part I

RMS - Modern History - 1498 AD to 1757 AD

RMS - Modern History - 1858 AD to 1919 AD

RMS - Geography - Interior of the Earth & Geomorphic Processes

RMS - Geography - Universe and Earth and Basic concepts on Earth

RMS - Economy - Indian Agriculture - Part I

RMS - Economy - Fundamentals of the Indian Economy

RMS - Polity - Union & its territories and Citizenship

RMS - Polity - Constitution & its Salient Features and Preamble

Learning Support Session - ANSWER writing MASTER Session

Learning Support Session - How to Read Newspaper?

Mastering Art of writing Ethics Answers

Mastering Art of Writing Social Issues Answers

Answer Review Session

UPSC CSE 2026 Form Filling Doubt Session

Mentoring Session (2024 - 25) - How to Write an ESSAY?

Social Issues Doubts and Mentoring Session

Ethics & Essay Doubts and Mentoring Session

Geography & Environment Doubts and Mentoring Session

History Doubts and Mentoring Session

Economy & Agriculture Doubts and Mentoring Session

Online Orientation Session

How to Read Newspaper and Make Notes?

Mains Support Programme 2025-(2)

Mains Support Programme 2025- (1)

Polity & International Relations Doubts and Mentoring Session

Mentoring Sessions (2024-25) - How to DO REVISION?

Learning Support Session - How to Start Preparation?

RMS - Geography - World Mapping

Mentoring Session (2024-25) - How to Make Notes?

General Mentoring Session (GMS )

Mentoring Session (2025-26) - How to write an Answer?

Article

14 Mar 2026

Why in news?

The ongoing West Asia conflict has highlighted the growing dangers faced by commercial sailors, particularly Indian seafarers, as tankers and merchant ships near the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz come under attack.

At least three Indian sailors have been killed, and industry experts warn of rising cases of “abandonment,” where shipowners stop supporting crews and vessels.

Indians, who make up about 15% of the global seafarer workforce, account for the highest number of abandoned sailors, with 1,125 cases reported in 2025, nearly 18% of global abandonment incidents.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Meaning of Seafarer Abandonment

- Reasons Behind Seafarer Abandonment

- Recent Cases of Abandoned Indian Seafarers

- Why Indian Seafarers Are More Vulnerable to Abandonment

- Protections and Support Mechanisms for Seafarers

Meaning of Seafarer Abandonment

- Seafarer abandonment occurs when shipowners stop providing support to crew members, leaving them stranded without wages, food, medical care, shelter, or means to return home.

- The Maritime Labour Convention (MLC), 2006 defines abandonment as the failure of shipowners to fulfil these essential responsibilities.

- For many seafarers, particularly those from low-income backgrounds, leaving an abandoned vessel is difficult because they may have already paid significant amounts to agents for employment or training.

- Port regulations or visa restrictions often prevent abandoned sailors from going ashore, forcing them to remain on board ships without support while hoping for assistance from shipowners or authorities.

Reasons Behind Seafarer Abandonment

- Shipowners may abandon their crews when faced with rising operational costs, volatile freight rates, heavy debts, bankruptcy, or geopolitical conflicts.

- In such situations, some owners choose to cut ties rather than pay wages, maintain vessels, or arrange repatriation for crew members.

- Role of the “Flag of Convenience” System

- A major factor enabling abandonment is the Flag of Convenience (FOC) system, under which ships register in countries offering lenient regulations, lower taxes, and weaker labour protections.

- This allows shipowners to bypass strict safety and labour standards.

- FOC registrations often hide the real ownership of vessels, enabling unscrupulous operators to avoid accountability and abandon ships and crews without facing legal consequences.

- According to the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), about 30% of the global merchant fleet sails under FOCs, and 90% of abandoned ships in 2024 were registered under such flags.

- Panama recorded the highest number of abandonment cases in 2025.

- Impact of the West Asia Crisis

- Experts warn that ongoing conflict in West Asia could worsen the situation.

- Financial stress on shipping companies operating in the region may increase the risk of more vessels and seafarers being abandoned in the future.

Recent Cases of Abandoned Indian Seafarers

- Several recent incidents highlight the growing problem of Indian seafarers being stranded on vessels in conflict-prone or unstable maritime regions.

- MV Manali (March 2026): Twenty Indian sailors and two others were stranded near Bandar Abbas Port in Iran during active bombings and appealed for rescue through social media.

- During abandonment, food, fuel, and drinking water often become scarce, forcing crew members to depend on nearby ports or external assistance for basic supplies.

- Regions with Frequent Abandonment Cases - Abandonments frequently occur in high-traffic or politically unstable maritime zones, including Turkey, the UAE, and the broader Gulf region, particularly near conflict-affected waters.

- Repatriation Efforts - Between 2025 and 2026, more than 100 Indian seafarers were repatriated from 14 vessels stranded in ports such as Sharjah (UAE), Tartus (Syria), Shinas (Oman), and Qatar.

Why Indian Seafarers Are More Vulnerable to Abandonment?

- Many Indians view seafaring as a pathway out of poverty, especially in smaller towns and rural areas where maritime salaries are significantly higher than local earnings.

- A rise in rogue recruitment agents has worsened the problem. These agents often charge large fees for fake job placements, forged certificates, or non-existent opportunities, leaving recruits financially burdened and vulnerable.

- Experts point to regulatory weaknesses, such as the ease of obtaining a Continuous Discharge Certificate (CDC) through short courses, which creates unrealistic expectations of guaranteed employment.

- With more recruits entering the maritime sector than available jobs, many Indian sailors end up working on high-risk or poorly regulated vessels, increasing their chances of abandonment.

Protections and Support Mechanisms for Seafarers

- International Support Through ITF - Abandoned seafarers can seek assistance from International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) inspectors, who help with wage negotiations, legal support, and repatriation.

- Assistance from Indian Authorities - Indian seafarers can contact the Directorate General of Shipping (DG Shipping) through its round-the-clock helpline for embassy assistance, emergency funds, and grievance redressal. Complaints can also be filed through the regulator’s website.

- Preventive Measures for Seafarers - Experts advise sailors to verify Recruitment and Placement Service Licensees (RPSL), avoid agents demanding fees, and ensure contracts are genuine. Early contact with welfare organisations can help prevent severe crises.

- Role of the Directorate General of Shipping - In India, the DG Shipping oversees verification of ships, shipowners, and recruitment agencies to ensure compliance with maritime regulations and protection of seafarers’ rights.

Article

14 Mar 2026

Why in news?

The Supreme Court ruled that income alone cannot determine the creamy layer among OBCs and addressed the issue of equivalence between PSU/private sector employees and government employees in this context.

Those classified as part of the creamy layer are not eligible for OBC reservation benefits, and the ruling clarifies long-standing uncertainties regarding the criteria used for such classification.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Supreme Court Clarifies Creamy Layer Criteria for OBCs

- Origin and Evolution of the OBC Creamy Layer Concept

- DoPT Clarifications on OBC Creamy Layer: 1993 Guidelines and 2004 Interpretation

- Income Criteria in OBC Creamy Layer and EWS Quota

- Beneficiaries of the Supreme Court’s OBC Creamy Layer Ruling

Supreme Court Clarifies Creamy Layer Criteria for OBCs

- Background of the Case - The SC delivered its verdict on petitions challenging a 2004 Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) letter that interpreted the creamy layer criteria under the 1993 Official Memorandum (OM) on OBC reservations.

- Issue with the 2004 Clarification - The 1993 OM excluded salary and agricultural income from the income/wealth test for determining creamy layer status. However, the 2004 DoPT letter included salary income of PSU and private sector employees, leading to differential treatment compared to government employees.

- Court’s Observation on Equality - The Bench held that excluding some candidates from reservation solely based on salary income—without considering the nature or level of employment—creates artificial distinctions among similarly placed OBC members.

- Ruling Against Discriminatory Treatment - The Court ruled that treating children of PSU or private sector employees differently from government employees amounts to hostile discrimination. Such unequal treatment of similarly placed individuals violates the constitutional guarantee of equality under Articles 14, 15, and 16.

Origin and Evolution of the OBC Creamy Layer Concept

- Introduction through the Mandal Verdict - The concept of the ‘creamy layer’ among OBCs was introduced by the Supreme Court in the 1992 Indra Sawhney vs Union of India (Mandal) judgment. The aim was to exclude the more advanced sections of OBCs from reservation benefits.

- 1993 Government Guidelines - Following the ruling, the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT) issued a circular in September 1993, defining the criteria for identifying the creamy layer within OBCs.

- Categories Included in the Creamy Layer - The guidelines identified several categories as creamy layer, including individuals holding constitutional posts, Group A/Class I and Group B/Class II government officers, PSU employees, Armed Forces officers, professionals, businesspersons, and property owners, along with those meeting the income/wealth criteria.

- Service-Based Criteria for Government Employees - Under these rules, children of Group A officers or those promoted to Group A before the age of 40 are excluded from OBC reservation benefits. Similarly, if both parents are Group B direct recruits, their children fall under the creamy layer.

- Criteria for Armed Forces Personnel - For the Armed Forces, officers up to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel remain eligible for OBC reservation benefits, while those holding higher ranks are classified under the creamy layer.

- Income Criterion for Non-Government Sector - For individuals outside government employment, the creamy layer was initially defined as those earning more than ₹1 lakh annually in 1993. This limit has been periodically revised and currently stands at ₹8 lakh per year since 2017.

DoPT Clarifications on OBC Creamy Layer: 1993 Guidelines and 2004 Interpretation

- The 1993 OM issued by the DoPT laid down the criteria for identifying the creamy layer among OBCs, including service-based categories and income thresholds to exclude the more advanced sections from reservation benefits.

- In October 2004, the DoPT issued a clarification stating that for employees in organisations where equivalence with government posts had not been determined, creamy layer status would be assessed based on parental income from salaries and other sources.

- The clarification provided that if income from salary or other non-agricultural sources exceeded ₹2.5 lakh per year for three consecutive years (the then creamy layer limit), their children would be treated as belonging to the creamy layer.

- Although issued in 2004, the clarification was not strictly implemented until 2014.

- It began to be applied effectively from the Civil Services Examination (CSE) 2015, when the DoPT started verifying caste certificates using these criteria.

- The Union government had also considered a proposal to establish equivalence between posts in government organisations, public sector enterprises, universities, and private sector jobs for determining creamy layer status.

- However, the proposal did not progress to the Cabinet stage.

Income Criteria in OBC Creamy Layer and EWS Quota

- The 1993 DoPT circular clearly stated that income from salary and agricultural land would not be counted while determining the income and wealth criteria for identifying the creamy layer among OBCs.

- During hearings on petitions challenging the EWS reservation introduced in 2019, the Supreme Court questioned why the income limit for EWS and OBC creamy layer was the same at ₹8 lakh.

- The government explained, based on the Ajay Bhushan Pandey Committee, that the two criteria differ in their calculation.

- For OBC creamy layer determination, income from salary and agriculture is excluded, whereas for EWS eligibility, income from all sources, including salary and agricultural income, is included.

Beneficiaries of the Supreme Court’s OBC Creamy Layer Ruling

- Impact on Future Candidates - The ruling will benefit candidates appearing in upcoming examinations, as the revised interpretation of the creamy layer criteria may allow more OBC candidates to claim reservation benefits.

- Relief for Existing Candidates in Services - Candidates already selected in government services may also benefit. Their service allocation or cadre placement could be revised, potentially enabling them to secure higher-ranked services or different cadres based on their updated OBC status.

- Opportunities for Previously Unallocated Candidates - Some candidates who could not previously secure a service may now receive service allocation if their rank improves after being recognised as non-creamy layer OBC candidates.

- Creation of Supernumerary Posts - The Supreme Court has directed the government to create supernumerary posts if necessary to accommodate eligible candidates affected by the ruling, provided they meet the required eligibility conditions.

Article

14 Mar 2026

Context:

- Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s visit to India marked a significant improvement in bilateral relations after tensions during Justin Trudeau’s tenure. The visit focused on practical outcomes while avoiding contentious past issues.

- Canada has adopted a pragmatic approach, managing domestic political sensitivities while cautiously rebuilding its relationship with India.

- This article highlights the renewed momentum in India–Canada relations following Prime Minister Mark Carney’s visit, focusing on economic cooperation, critical minerals, energy partnerships, and pragmatic diplomacy.

Economic Focus in the India–Canada Engagement

- The renewed engagement between India and Canada comes amid significant global geopolitical and economic disruptions.

- Canada faces pressure from the United States due to supply-chain dependence and evolving tariff policies, while conflicts in Europe, West Asia, and the Levant have unsettled global economic stability.

- Shared Interest in Stability and Growth

- India and Canada share a common objective of avoiding geopolitical conflicts and focusing on economic growth and national development.

- However, given the interconnected nature of global supply chains, both countries recognise that they cannot remain completely insulated from global disruptions.

- Both nations view diversification in trade, energy, investment, and security partnerships as essential to reducing vulnerabilities and strengthening economic resilience.

Key Outcomes of the Carney Visit

- Prime Minister Mark Carney’s visit resulted in at least eight agreements and contracts across important sectors.

- A major development was the signing of terms for the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), establishing a framework for future trade negotiations.

- Another important outcome was a memorandum of understanding under the Australia–Canada–India Technology and Innovation Partnership.

- This is aimed at promoting collaboration in technology and innovation and strengthening Canada’s engagement with Indo-Pacific partners.

Expanding Strategic Cooperation Between India and Canada

- Broader Areas of Collaboration - India and Canada signed additional agreements to strengthen cooperation in research partnerships, cultural exchanges, and food and nutrition sectors, expanding the scope of bilateral engagement beyond trade and investment.

- Key Agreements on Uranium and Critical Minerals - Two major outcomes of the visit were a commercial contract between India’s Department of Atomic Energy and Canada’s Cameco for uranium ore supply, and an MoU on critical minerals cooperation.

- Importance of Critical Minerals - Critical minerals are essential for advanced technologies, clean energy systems, and modern industries. With global demand rising, countries are increasingly seeking to secure stable supply chains for these resources.

- Reducing Dependence on China - Currently, supply chains for many critical minerals are concentrated in a few countries, particularly China. China’s use of mineral supply chains as geopolitical leverage has prompted other nations to diversify sources and reduce strategic dependence.

- Alignment with Emerging Strategic Initiatives - India–Canada cooperation on critical minerals aligns with broader initiatives such as the U.S.-led Pax Silica coalition, aimed at strengthening collaboration in semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and secure technology supply chains.

Energy Cooperation at the Core of India–Canada Engagement

- Energy cooperation emerged as a key focus in India–Canada relations, with both conventional and renewable energy gaining importance.

- Canada’s resource wealth complements India’s rapidly growing energy demand.

- India aims to expand clean energy usage to meet its sustainable development and zero-emission targets.

- Reducing dependence on external energy imports while increasing domestic production is crucial for long-term energy security.

- Expanding the Role of Nuclear Energy

- One effective strategy for achieving energy sustainability is expanding nuclear power in India’s energy mix.

- The Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill, 2025 represents a step toward strengthening nuclear energy development.

- Canada’s agreement to supply uranium ore concentrates provides long-term fuel security for India’s nuclear energy programme.

- Along with potential nuclear reactor cooperation with the United States, it can enhance India’s energy stability.

- Reducing Energy Vulnerabilities

- India’s heavy reliance on external energy sources has increased vulnerability amid global conflicts.

- The uranium deal with Canada supports India’s goals of reducing external risks, sustaining development, and achieving 100 GW of nuclear power capacity by 2047.

Conclusion

- Overall, the India–Canada reset reflects a shift toward pragmatic, deliverable-driven cooperation in trade, energy, technology, and critical minerals, strengthening strategic resilience amid evolving global economic and geopolitical challenges.

Article

14 Mar 2026

Why in the News?

- The Supreme Court recently observed that making paid menstrual leave mandatory by law may unintentionally harm women’s career prospects and reduce their employment opportunities.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Menstrual Leave (Debate in India, Global Practices, etc.)

- Court’s Judgement (Key Observations, Voluntary vs Legal Debate, Broader Issues, etc.)

Menstrual Leave in India

- Menstrual leave refers to leave granted to women during their menstrual cycle when they may experience severe physical discomfort, such as cramps or other medical conditions.

- The issue has increasingly become part of discussions on gender equality, workplace welfare, and labour rights.

- India does not currently have a nationwide law mandating menstrual leave. However, certain initiatives exist at the institutional or regional level. For example:

- Some educational institutions have introduced menstrual leave policies for students.

- Certain state governments have provided limited leave provisions in schools or universities.

- Several private companies have voluntarily implemented menstrual leave policies.

- These initiatives reflect growing awareness of menstrual health issues in workplaces and educational institutions.

Global Practices on Menstrual Leave

- Several countries have adopted policies related to menstrual leave, though their design and implementation vary. For instance:

- Spain introduced a law in 2023 allowing women to take 3-5 days of menstrual leave, with the cost borne by the government.

- Japan introduced menstrual leave legislation as early as 1947.

- South Korea, Indonesia, China, and Zambia also have provisions that allow menstrual leave under certain conditions.

- These international examples illustrate different approaches to addressing menstrual health in workplaces.

Supreme Court’s Observations on Mandatory Menstrual Leave

- The debate gained attention after a petition sought directions from the Supreme Court to introduce a uniform law granting paid menstrual leave to women workers and female students across the country.

- The Supreme Court Bench, headed by Chief Justice of India Surya Kant, observed that a mandatory legal provision for menstrual leave could negatively impact women’s careers.

- The Court highlighted several potential risks:

- Impact on Hiring Decisions: Employers might become reluctant to hire women if they are required to provide additional mandatory leave every month.

- Reduced Workplace Responsibilities: There is concern that employers may hesitate to assign major responsibilities to women if they perceive them as frequently unavailable during certain periods.

- Career Growth Concerns: The Court observed that mandatory leave policies might inadvertently create a perception that women are less capable of handling demanding roles.

- These observations were based on the broader realities of the labour market and workplace dynamics.

- Ultimately, the Court disposed of the petition and asked the Central Government to consider the representation and explore the possibility of framing an appropriate policy in consultation with stakeholders.

Distinction Between Voluntary Policies and Legal Mandates

- While expressing concerns about a compulsory law, the Court made an important distinction between voluntary workplace policies and statutory mandates.

- The judges encouraged voluntary initiatives by employers or institutions that support women employees. Such policies allow organisations to adapt to their workforce needs without creating rigid legal obligations.

- For example, some private companies and educational institutions have already introduced menstrual leave policies. Similarly, certain states have implemented limited provisions for menstrual leave in educational institutions.

- The Court indicated that such voluntary approaches may provide support to women without negatively affecting employment opportunities.

Broader Issues in the Debate

- The discussion around menstrual leave highlights broader issues concerning gender equality in workplaces.

- Supporters argue that menstrual leave recognises biological realities and promotes workplace dignity for women. It can help women manage severe menstrual pain, which may otherwise affect productivity and health.

- Critics, however, argue that mandatory leave policies could reinforce gender stereotypes and discourage employers from hiring women.

- Therefore, policymakers must balance workplace equality, health considerations, and labour market realities while designing such policies.

Article

14 Mar 2026

Context:

- The Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) cylinder and pressure cooker have become enduring symbols of modern domestic life in India since the mid-20th century.

- Access to LPG not only represents technological progress and household welfare but also reflects deeper social dynamics related to class mobility, gender roles, and public policy.

- Government initiatives such as the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) have attempted to expand access to clean cooking fuel.

- However, global geopolitical developments—particularly tensions in West Asia and disruptions (around the Strait of Hormuz)—continue to affect LPG supply and affordability in India.

LPG in India - From Household Symbol to Welfare Instrument:

- LPG cylinder as a marker of modernity:

- Since the 1950s, LPG cylinders have become a cultural symbol of modern domestic life and rising living standards.

- In popular culture, the presence of LPG and pressure cookers signifies economic mobility, family well-being, and urban aspirations.

- Conversely, traditional wood-burning chulhas are often used in cinema and literature to portray poverty and deprivation.

- LPG as a tool of welfare policy:

- The Government of India launched the PMUY in 2016 to provide clean cooking fuel connections to poor and rural households, particularly women.

- Objectives include reducing indoor air pollution, improving women’s health, reducing drudgery associated with firewood collection, and promoting clean energy transition.

- The scheme also carries strong political and welfare symbolism, presenting LPG access as a marker of development and dignity.

Global Geopolitics and India’s LPG Security:

- Dependence on imports:

- India relies heavily on imported LPG to meet domestic demand.

- Approximately 90% of LPG imports pass through the Strait of Hormuz, a crucial maritime energy corridor.

- Geopolitical risks:

- Conflicts in West Asia, including tensions involving Iran and Israel, threaten supply routes.

- Any disruption in the Strait of Hormuz can trigger supply shortages, price volatility, and energy security concerns.

- These risks highlight the vulnerability of welfare schemes like PMUY to global energy geopolitics.

- Economic impact beyond households:

- LPG shortages affect not only households but also the service economy, including restaurants, hotels, and small food businesses.

- These sectors may have to curtail operating hours, highlighting the broader economic importance of LPG supply stability.

Social Dimensions of Energy Access:

- Class and poverty:

- Poor households are more dependent on biomass fuels (wood, dung, crop residues).

- Burning biomass contributes to indoor and outdoor air pollution, disproportionately affecting the poor due to crowded settlements, poor ventilation, and high population density.

- Caste-based inequality:

- Access to LPG shows stark disparities across social groups. For example, upper-caste households have significantly higher LPG adoption.

- SC/ST households face barriers such as marginalised settlements, poor infrastructure and transport, and difficulty in accessing LPG distribution networks.

- Thus, energy access intersects with caste and spatial inequality.

- Gender dimension:

- Women and girls bear the greatest burden of biomass fuel usage due to their traditional role in cooking.

- Consequences include higher exposure to indoor air pollution, and respiratory illnesses and long-term health risks.

- Despite this, household fuel decisions are often taken by men, reflecting gendered power structures.

Women’s Empowerment Through LPG Access:

- Health benefits: Reduced exposure to smoke and particulate matter lowers risks of respiratory diseases, eye irritation, and cardiovascular problems.

- Time and labour savings: LPG reduces the time spent on collecting firewood and long cooking processes.

- Economic and social empowerment:

- Saved time allows women to pursue income-generating activities, participate in community life, and enjoy leisure and better health.

- Control over time enhances personal autonomy and life opportunities for women.

Challenges and Way Forward:

- Import dependence: Heavy reliance on LPG imports exposes India to global supply disruptions and price shocks.

- Diversification of energy sources: Reduce import dependency by expanding domestic LPG production, and alternative clean fuels (biogas, electric cooking).

- Infrastructure and distribution gaps: Remote and marginalised settlements often lack efficient LPG distribution networks.

- Inclusive energy access: Improve LPG distribution infrastructure in remote and marginalised communities.

- Social inequality: Persistent caste, class, and gender disparities in access to clean fuel.

- Promote clean cooking alternatives: Encourage solar, induction cooking, and community biogas systems in rural areas.

- Affordability of refills: Even with subsidies, refill costs discourage sustained usage among poor households.

- Strengthening PMUY implementation: Ensure affordable refills and continuous usage, not just connection coverage.

- Geopolitical vulnerability: Disruptions in energy chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz can undermine domestic welfare policies.

- Strategic energy security: Develop strategic LPG reserves and diversify import routes to mitigate geopolitical risks.

Conclusion:

- The LPG cylinder represents far more than a household utility in India—it embodies public health, gender justice, social mobility, and development aspirations.

- Programmes such as PMUY have expanded access to clean cooking fuel, yet structural inequalities and geopolitical vulnerabilities continue to shape outcomes.

- Ensuring reliable, affordable, and equitable access to clean energy is essential not only for improving household welfare but also for advancing inclusive development and energy security in India.

Article

14 Mar 2026

Context

- In the late twentieth century, the Washington Consensus emerged as a dominant framework guiding economic reform in developing countries.

- Coined by John Williamson in 1989, the term described ten policy prescriptions widely supported by institutions in Washington as remedies for economic crises.

- These reforms emphasised fiscal discipline, market liberalisation, privatisation, and deregulation, aiming to stabilise economies and stimulate growth.

- Today, the Washington Consensus is seen less as a universal blueprint and more as a historically specific framework whose legacy continues to shape debates about development and global economic governance.

Origins and Core Principles of the Washington Consensus

- The Washington Consensus emerged during severe debt crises in Latin America and other developing regions.

- International institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank promoted reforms intended to restore macroeconomic stability and encourage market-driven growth.

- The ten policy prescriptions included:

- Fiscal discipline

- Reordering public expenditure,

- Tax reform, interest rate liberalisation,

- Competitive exchange rates,

- Trade liberalisation,

- Foreign direct investment liberalisation,

- Privatisation of state enterprises,

- Deregulation, and Secure Property Rights.

- Together these reforms formed a policy framework often summarised as liberalise, privatise, and deregulate.

Implementation and Global Impact

- The Washington Consensus operated largely through loan conditionalities imposed by international financial institutions.

- Countries facing fiscal or balance-of-payments crises often adopted structural reforms in exchange for financial assistance from the IMF or the World Bank.

- These reforms reshaped national economies by encouraging trade openness, financial liberalisation, and private sector expansion.

- In some countries they contributed to improved macroeconomic stability and renewed growth. Yet outcomes varied widely across regions.

Critiques and Structural Limitations

- A major criticism of the Washington Consensus was its rejection of industrial policy, which involves state support for strategic domestic industries.

- Trade rules under the World Trade Organization restricted policy tools such as subsidies and investment regulations, limiting the ability of developing countries to nurture emerging sectors.

- This restriction contrasted sharply with the historical experience of successful industrial economies.

- Countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan relied heavily on state-led development, strategic protection, and targeted industrialisation during their formative years.

- Structural adjustment policies also produced significant social consequences. Cuts in public spending weakened public services, increased economic inequality, and intensified poverty in several regions.

Political Backlash and the Decline of the Consensus

- By the late 1990s, dissatisfaction with the Washington Consensus had grown widespread.

- Protests against globalisation and international financial institutions spread across many parts of the Global South.

- The divisions were also visible in global trade negotiations, including the 1999 Seattle WTO protests and the 2003 Cancún WTO Ministerial Conference.

- These confrontations highlighted tensions between developed and developing nations over trade rules and development priorities.

- After the 2008 financial crisis, scepticism toward liberalisation expanded within advanced economies as well.

- Political movements expressing frustration with globalisation emerged in the West, including the Make America Great Again movement and the referendum leading to Brexit.

- These developments revealed widespread disillusionment with economic globalisation and its perceived social costs.

The Emergence of a Post-Washington Consensus

- The twenty-first century has witnessed the gradual emergence of a post-Washington consensus, which recognises that markets alone cannot ensure inclusive development.

- Contemporary economic thinking emphasises institutional strength, public investment, social safety nets, and redistributive policies.

- Governments increasingly focus on education, healthcare, infrastructure, and innovation systems to support long-term development.

- Strategic industrial policy, once dismissed, has regained importance in fostering technological capabilities and competitive industries.

- Alternative models have also gained prominence. The state-led development strategy associated with China demonstrates how state intervention, industrial strategy, and controlled liberalisation can drive rapid economic transformation.

Conclusion

- The Washington Consensus once offered a seemingly universal formula for development based on liberalisation, privatisation, and deregulation.

- Over time, however, financial crises, inequality, and political resistance revealed the limitations of a single policy template.

- Contemporary economic governance reflects a more pragmatic, context-sensitive, and policy-diverse approach.

- Governments now combine market mechanisms with state intervention, adapting strategies to their institutional capacities and national priorities.

- The decline of the Washington Consensus therefore marks not the end of globalisation, but the end of the belief in a single universal model of development.

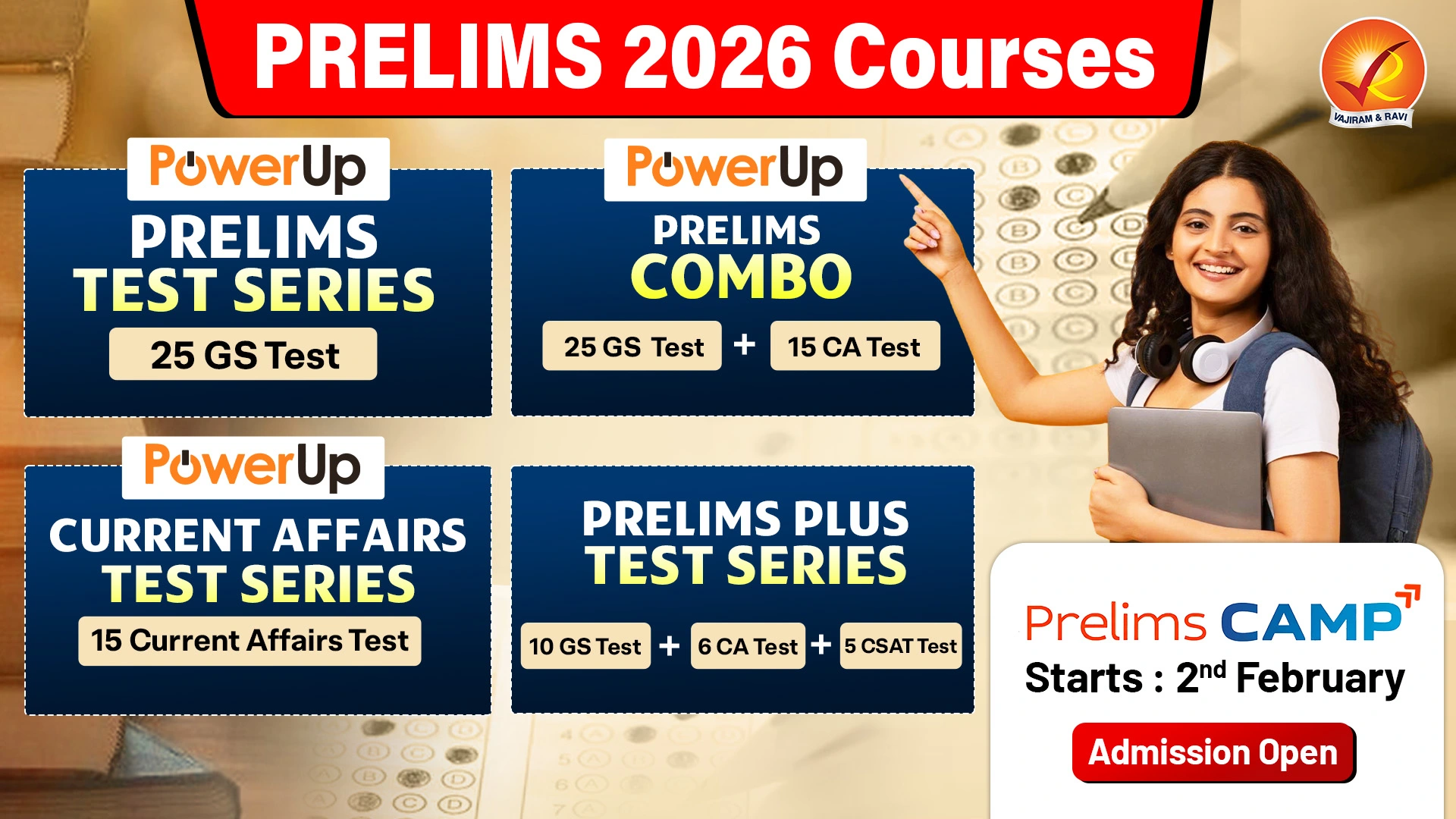

Online Test

14 Mar 2026

CAMP-PT-CA-07

Questions : 50 Questions

Time Limit : 0 Mins

Expiry Date : May 31, 2026, 11:59 p.m.

Online Test

14 Mar 2026

CAMP-PT-CA-07

Questions : 50 Questions

Time Limit : 0 Mins

Expiry Date : May 31, 2026, 11:59 p.m.

Online Test

14 Mar 2026

CAMP-HINDI-CSAT-22

Questions : 40 Questions

Time Limit : 60 Mins

Expiry Date : May 31, 2026, 11:59 p.m.

Online Test

14 Mar 2026

CAMP-HINDI-CSAT-22

Questions : 40 Questions

Time Limit : 0 Mins

Expiry Date : May 31, 2026, 11:59 p.m.