Context

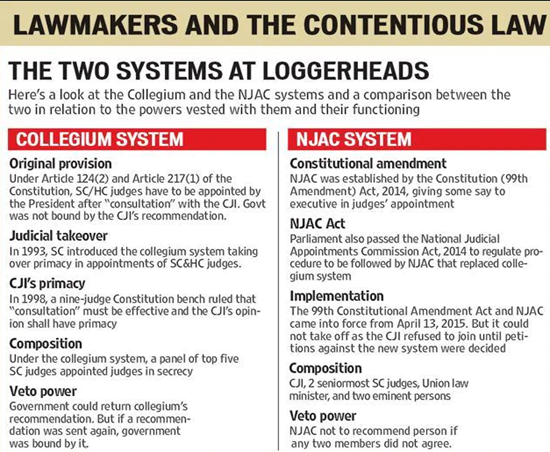

- The Vice president of India recently remarked that the Supreme Court’s 2015 verdict, which struck down the NJAC and the 99th Constitutional Amendment, 2014, severely compromised parliamentary sovereignty and disregarded the people’s will.

- Earlier, Union Law Minister had said that the Collegium system of appointing judges was “opaque”, “not accountable” and “alien” to the Constitution.

- The article highlights how disturbing these attacks on the Collegium system and the SC verdict are and illustrates the inadequacies of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC).

The Constitution (99th Amendment) Act, 2014

- It bought the following changes to replace the collegium system and introduced 3 primary Articles as follows:

- Article 124A: It created a constitutional body namely National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) to replace the collegium system.

- Article 124B: It conferred the NJAC powers to make appointments.

- Article 124C: It empowered Parliament to regulate the NJAC’s functioning.

- In 2014, the Parliament unanimously voted in favour of NJAC Act, replacing the collegium system with the NJAC.

The NJAC Act

- Appointment procedure: The NJAC was to recommend the Chief Justice of India and Chief Justices of the HCs based on seniority.

- The SC and HC judges were to be recommended based on ability, merit and other criteria.

- NJAC Panel: It was a 6-member panel chaired by the CJI and with two of the senior-most judges of the SC as its members.

- The Union Law Minister and two “eminent persons” were the other three. One of the eminent members had to be nominated from persons belonging to the SC, ST, OBC or should be a woman.

- Any 2 members of the panel can veto a recommendation.

Why NJAC was challenged?

- In 2015, the Supreme Court AdvocatesonRecord Association (SCAORA) filed a plea against NJAC arguing that it took away the primacy of the judiciary’s collective opinion, as its recommendation could be vetoed.

- The petitioner also argued that NJAC “severely” damaged the basic structure (independence of the judiciary) of the Constitution.

- 4th Judge Case 2015: The NJAC and the 99th Amendment was struck down by SC bench on the grounds of endangering judicial independence.

- This led to the restoration of the collegium system under which appointments and transfers of judges are decided by a forum of CJI and the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.

Contentions related to NJAC

- No casting vote for CJI: Under Article 124A, the NJAC comprised of an even number of members but the Chairperson - the CJI, had no casting vote. There was no clarity over a tie and thus a deadlock was obvious.

- Eminent persons may lack expertise: Unlike other Central Acts, where the “eminent persons” appointed as part of a committee must have expertise in the subject that the statute covers, the NJAC does not require the eminent person to have any expertise.

- It implied one-third of the NJAC could be constitutionally unaware of the functioning of the SC or the HCs and yet decide the destiny of our higher judiciary.

- Procedure of appointment included many vaguely worded terms: The NJAC Act required the commission to recommend the senior-most judge of the SC as the CJI “if s/he is considered fit to hold the office”. However, it did not define what constituted fitness to hold office.

- Veto provision: Under NJAC Act, no recommendation could be made by the NJAC if any two of the six members disagreed. This could have created chaos in the appointment process and enabling the executive to completely dominate the judiciary.

- Peculiar selection procedure for HC judges: The Chief Justice and two senior-most judges of every HC had to nominate persons to the NJAC for appointment as HC judges.

- The NJAC could also simultaneously nominate persons for appointment as HC Judges. The split may have arisen if two sets of nominees were different.

- Further, the NJAC had to “elicit in writing” the views of the Governor and the Chief Minister in appointment of HC judges. There was no clarity over whose view would prevail if these two took opposite views.

- NJAC determining criteria of suitability: The 99th amendment bestowed upon NJAC the power to frame regulations laying down the criteria of suitability, and the procedure of appointing judges of the SC and the HCs.

- These regulations had to be tabled before both Houses of Parliament that had the power to nullify these regulations or modify them which made the appointment process inefficient.

SC’s reply to recent criticism of Collegium system

- The power of Parliament to enact a law is subject to scrutiny by the courts that are the “final arbiter” of the law under the Constitutional scheme.

- The average clearance rate of the Collegium is about 50%, indicating that the government’s view is taken into account while appointing judges.

Way forward

- Reformed NJAC: The NJAC needs to be amended to make sure that the judiciary retains independence in its decisions and re-introduced with judges constituting a clear majority in the Commission.

- Detailed guidebook: A written manual should be released by the SC which should be followed during appointments.

- Recording minutes of Collegium: The deliberations of the Collegium could be video-recorded and archived and all meetings should be in the public domain in order to ensure transparency and a rule-based process.

- Specified criteria: Like regional representation, seniority, gender, etc., to elevate judges and advocates to the SC instead of leaving it solely to the unanimity of the Collegium could help avoid disagreements in the future.

- UK Model: A special selection commission undertakes the exercise of selecting the various applicants for the post of judges, the qualifications and the procedure being prescribed.

- The selected nominees are provided in a report to the Lord Chancellor, who recommends a name to the Prime Minister, who in turn advises the King to make the appointment.

- US Model: Under the US Constitution, the President has the power to make a nomination to the Supreme Court and the Senate has the task to approve a candidate to enforce the concept of checks and balances.

Conclusion

- India needs to restore the credibility of the higher judiciary by making the process of appointing judges transparent and democratic (SC in its 2015 verdict said “all is not good with the Collegium”).

- It is time to consider establishing a permanent, independent organisation to institutionalise the process while preserving the judiciary's independence by ensuring judicial primacy, diversity, professional competence and integrity.