Context: The article highlights concern over the high judicial pendency in India and suggests corrective measures to rectify it.

Statistics related to pendency in Indian Judiciary

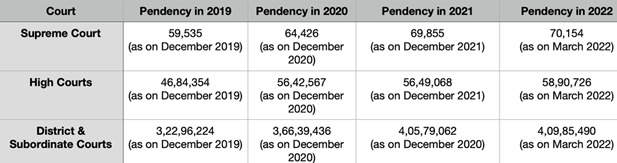

- At over 47 million, India has the largest number of pending court cases in the world.

- As per the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG), 57,987 cases in Supreme Court and 49 lakh cases are pending in High Courts

- Also 2.4cr cases are pending cases in India’s district courts, out of which 23 lakh (9.58%) have been pending for over 10 years, and 39 lakh (16.44%) have been pending for between 5 and 10 years.

- A Law Commission report in 2009 had quoted that it would require 464 years to clear the arrears with the present strength of judges.

- A 2018 paper by NITI Aayog said it would take more than 324 years to clear the backlog.

Causes of judicial pendency and solutions to reform judicial system

- Government - the biggest litigant: The Centre and state governments are party to 46% of the pending cases.

- Thus, a simple negative list which identifies instances in which government and its agencies are barred from going to court would be helpful to avoid futile litigation.

- Judge strength: As of 2021, India had 21.03 judges per million people compared to the UK with 51 and the US with 107 judges per million. Hence India needs more judges for speedy justice delivery.

- The 120th Law Commission of India report has suggested a judge strength fixation formula.

- India should utilize its most experienced judges since present retirement age (62 for HC judges and 65 for SC judges in contrast with 75 in UK or Canada) was fixed when life expectancy was lower.

- Judicial appointments: The tussle between the executive and the judiciary over judicial appointments must be resolved on a war footing. The collegium system of judges appointing other judges should be replaced with a more viable scheme.

- The Constitution of the All-India Judicial Services can also help India establish a better judicial system.

- Administrative burden: The Indian judges spend majority time in scheduling hearings, deciding admission, etc., unlike in developed countries where administrative tasks of courts are supported by an external agency.

- India can emulate the same with a separate professional agency with administrative expertise, specialization, and modern management practices and technologies.

- The Union government had suggested Indian Courts and Tribunal Services (ICTS) - an authority charged with supervising and fulfilling the administrative requirements of the courts.

- This will increase the productivity of the court system and assure that judges are left free to perform the core task of handling cases and delivering judgments.

- Frivolous litigation: Certain categories of cases such as dishonouring of cheques or landlord-tenant disputes are voluminous and clog the system.

- Thus, rules should be established for disincentivizing such litigations by imposing exceptionally heavy costs on losing party. This would lead to several frivolous disputes settled out of court.

- Poor judicial infrastructure: For example, many court complexes operate from rented premises. Ex CJI N V Ramanna has remarked that a National Judicial Infrastructure Corporation (NJIC) should be created for the standardization and improvement of judicial infrastructure.

- Technology constraints: Certain categories of cases can be moved permanently to an online disposal system, similar to online hearings during Covid-19 lockdown. The computer algorithms could also be used to manage the roster, thus eliminating bias.

- Issue of undertrials: Around 76% of prisoners in Indian jails are undertrials, i.e., three out of four prisoners are not even convicted.

- The SC recently directed the government to consider the introduction of Indian Bail Act to streamline the grant of bails, as done in various other countries like the UK.

- Frequent adjournments: A norm needs to be formed that once a date is fixed no adjournment should be possible unless the side that requests it is willing to pay the other side's legal costs along with a substantial penalty.

- Volume of appeals: Almost 40% of the working days of SC judges are consumed in determining admission of special leave petitions (SLPs) and as much as 90% of those SLPs are rejected. It leads to mammoth time wastage of SC.

- SLP provides the aggrieved party a special permission to be heard in apex court in appeal against any judgment or order of any Court/tribunal in the territory of India.

- Thus, Special Benches can be assigned for time-bound and quick disposal of SLPs.

- Poor management practices: The system of long vacations for courts is a colonial practice that should be done away for optimum justice delivery owing high pendency in courts today.

- Former CJI Lodha has recommended that instead of all the judges going on vacation at one time, individual judges should take their leave at different times through the year.

- It will ensure that the courts are constantly open and there are always benches present to hear cases.

- Absenteeism of judges: The productivity of judges should be reviewed periodically to have oversight upon absenteeism of judges.

- Ex CJI Ranjan Gogoi had proposed a “no leave formula” for judges during working days of the court.

- Those judges who failed to follow the formula would either withdraw his name from the judges list or judicial work is withdrawn from that errant member of the court. This should be emulated in lower courts also.

- Poor case flow management: The SC had drawn up a fine blueprint on case-management, on how to get more cases moving along. For instance, on three different tracks, i.e., fast track, normal track and slow track.

- Low number of Special courts: Special Courts can be established on specialised areas such as commercial cases can be transferred to the commercial division and the commercial appellate division of High Courts.

- Similarly, Special Courts within High Courts can be set up to address litigations pertaining to land, crime, traffic challans etc., in order to reduce the burden on main courts.

Earlier steps taken to reduce pendency

- Policy formulation: Adoption of “National Litigation Policy 2010” to transform government into an Efficient and Responsible litigant. All states formulated state litigation policies after National Litigation Policy 2010.

- Legal Information Management and Briefing System (LIMBS): It was created in 2015 with the objective of tracking cases to which the government is a party.

- Criminal reform: The SC had advised the Centre that criminals sentenced to imprisonment for 6 months or a year should be allocated social service duties rather than be sent to further choke the already overflowing prisons.

- Concept of Plea Bargaining: It was inserted as a new chapter in Criminal Procedure Code, 1973.

- Plea Bargaining means a pre-negotiation between the accused and the prosecution where the accused pleads guilty in exchange for certain concession by the prosecution.

- Its main objective is to reduce the time in criminal trial and give the accused a lesser punishment and helps in fast disposal of cases.

- Alternate dispute resolution (ADR): The Legal Services Authorities undertake pre-litigation mediation so that the inflow of cases into courts can be regulated. E.g., Lok Adalat for settling civil and family matter, Gram Nyayalayas to manage small claim disputes from rural areas, etc.

Conclusion

- Denial of ‘timely justice’ amounts to denial of ‘justice’ itself. Timely disposal of cases is essential to maintain rule of law and provide access to justice.

- Speedy trial is a part of right to life and liberty guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution.

- Hence a continuous formative assessment to come out of the judicial pendency crisis is the key to strengthen and reinforce the justice delivery system in India.