Context

- The architecture of fiscal federalism in India is designed around the constitutional obligation of resource sharing between the Union and the States.

- Central to this framework are the Finance Commissions (FCs), which periodically determine the share of Union tax revenues devolved to States and the formula used to distribute them.

- While the recommendations of fifteen FCs have been implemented, the Sixteenth FC’s report is awaited, and the broader system of transfers has come under scrutiny.

Central Transfers and Fiscal Autonomy

- Central transfers take three primary forms: tax devolution, grants-in-aid and Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS).

- Over time, concerns have grown that this system has progressively reduced fiscal autonomy for States.

- The Goods and Services Tax (GST) curtailed independent revenue-raising powers and created compensation dependencies, while GST rate cuts generated additional revenue shortfalls.

- At the same time, CSS expanded in scope, prescribing expenditure patterns and reducing flexibility for State-level prioritisation.

- Another contentious issue is the Union’s increasing reliance on cesses and surcharges, which are constitutionally excluded from the divisible pool.

- High-performing States also argue that FC recommendations privilege equity over efficiency, with frequent changes in weighting of variables such as population and income distance.

- These decisions have contributed to perceptions of arbitrariness, especially given persistent disparities in expenditure needs and fiscal capacity across regions.

Tax Contribution versus Collection

- Economically advanced States such as Maharashtra, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu argue that they contribute disproportionately to Union revenues while receiving relatively smaller shares through devolution.

- The challenge lies in distinguishing between where taxes are collected and where income is generated.

- Direct taxes are often recorded in States where corporate headquarters or high-income individuals file returns, rather than where economic value is actually created.

- Multi-State firms, labour mobility and complex inter-State transactions exacerbate this attribution gap.

- Examples illustrate these distortions: automobile firms based in Tamil Nadu produce for a national market, yet tax payments may be recorded in other States.

- Plantation companies headquartered in Kerala generate profits nationwide, though taxes accrue locally.

- These patterns underscore that direct tax collections are not a reliable measure of State-wise contribution.

GSDP as a Proxy for Tax Accrual and The Mismatch

- GSDP as a Proxy

- Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) provides a more accurate proxy for assessing the underlying tax base.

- Since GSDP reflects the scale of economic activity and assuming comparable tax administration efficiency across States, a State’s share in national GSDP can approximate its contribution to Union revenues.

- This relationship is especially strong for GST, a destination-based tax whose attribution across States aligns with consumption.

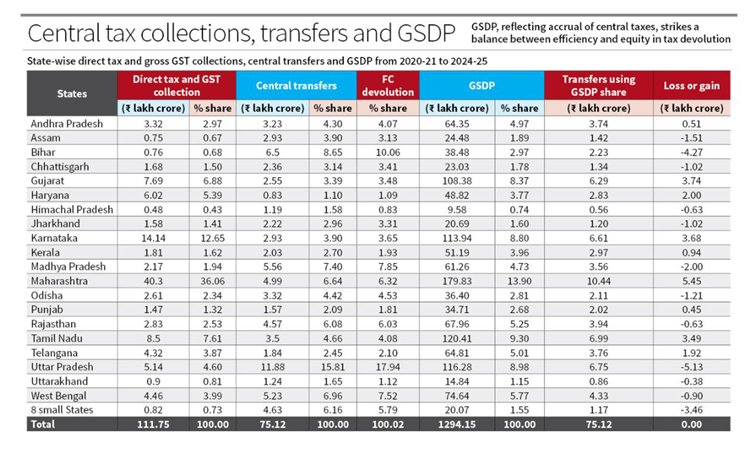

- From 2020–21 to 2024–25, the Union devolved 41 percent of gross tax revenues to States, supplemented through grants and CSS, amounting to ₹75.12 lakh crore.

- The Mismatch

- Uttar Pradesh received the largest share (15.81 percent), followed by Bihar (8.65 percent) and West Bengal (6.96 percent).

- However, these States accounted for only 4.6, 0.67 and 3.99 percent of combined direct and GST collections.

- In contrast, Maharashtra contributed 40.3 percent but received just 6.64 percent, while Karnataka and Tamil Nadu contributed 12.65 and 7.61 percent, receiving 3.9 and 4.66 percent respectively. These imbalances have intensified concerns about fairness.

- Correlation patterns further illuminate this mismatch. The Fifteenth FC’s devolution shares correlate strongly with actual transfers but weakly with tax collections.

- GSDP shares correlate strongly with collections and moderately with transfers, indicating that GSDP aligns contribution with redistribution.

- Only Haryana, Karnataka and Maharashtra show GSDP shares below tax shares, due to headquarters clustering.

- Tamil Nadu shows the opposite pattern, reflecting production whose taxes accrue elsewhere.

Potential Reforms and Redistribution Effects

- If central transfers were allocated purely on GSDP shares, nine of twenty major States would gain, with Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu benefiting most.

- Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh would experience the largest reductions.

- These changes would be moderate because GSDP shares differ less sharply from tax collection shares than current devolution outcomes.

Conclusion

- The debate over India’s central transfers is ultimately a contest between competing principles of federal design: equity, efficiency and legitimacy.

- The Indian system prioritises equity through redistribution, benefiting fiscally weaker States but generating dissatisfaction among high-contributing States.

- Increasing the weight of GSDP in the formula could better reflect economic contributions, enhance legitimacy and strengthen cooperative federalism without abandoning redistribution.