In News:

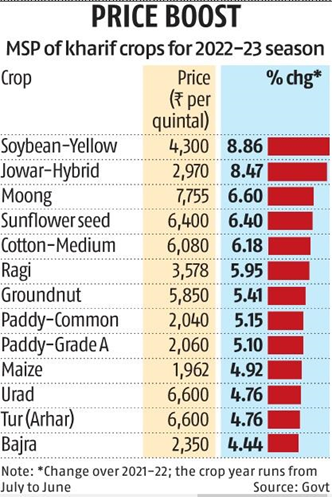

- The Central government recently raised the minimum support price (MSP) of kharif crops for the 2022-23 crop year (July-June) by around 4-9 per cent.

What’s in today’s article:

- About Kharif/Rabi Crops (Sowing seasons, Common Rabi/Kharif crops, etc.)

- About MSP (Origin, Purpose, Should it be given statutory backing, Implications, etc.)

About Kharif crops:

- The crops that are sown in the rainy season are called Kharif crops and it is also known as the summer or monsoon crop in India.

- The crops that are sown in the winter season are called Rabi crops.

- Kharif crops are usually sown with the beginning of the first rains in July, during the south-west monsoon season.

- The sowing time may vary in the different states of India as it depends on the arrival of monsoon.

- For example, in southern states like Kerala, the seeds are usually sown towards the end of May and in northern states like Punjab, Haryana the seeds are sown in the month of June.

- These crops are dependent on the quantity of rainwater as well as its timing.

- Harvesting takes place in the months of September or October.

Common Kharif crops:

- Cereal crops:

- Rice, Bajra, Jowar, Maize (corn), Millet and Soyabean

- Fruit crops:

- Muskmelon, Sugarcane, Watermelon, Orange

- Seed/Grain crops:

- Arhar (tur), Black gram (urad), Cotton, Cowpea, Green gram (moong), Groundnut, Guar, Moth bean, Mung bean, Sesame, Urad bean

- Vegetable crops:

- Bitter gourd (karela), Bottle gourd, Brinjal, Chilli, Ladyfingers, Sponge Gourd, Tinda, Tomato, Turmeric, French beans

About Rabi crops:

- The crops that are sown in the winter season are called Rabi crops and it is also known as the winter crop in India and Pakistan.

- Rabi crops are usually sown in October or November.

- Rabi crops are cultivated in the dry season so timely irrigation is required to grow these crops.

- Harvesting takes place in the months of March or April.

Common Rabi crops:

- Cereal crops:

- Barley, Gram, Rapeseed, Mustard, Oat, Wheat and Bajra

- Fruit crops:

- Almond, Banana, Ber, Dates, Grapes, Guava, Kinnow, Lemon/Citrus, Mangoes, Mulberries, Orange

- Legumes/lentils (dal) crops:

- Chickpea, Lobias, Masoor, Mung bean, Pigeon pea, Toria, Uradbean

- Seed/grain crops:

- Alfalfa, Coriander, Cumin, Fenugreek, Linseed mustard, Isabgol, Sunflower, Bengal gram, Red gram

Minimum Support Price (MSP):

- In 1966-67, as a part of extensive agricultural reforms, MSP was introduced for the first time by the Central Government.

- Minimum support price (MSP) is a “minimum price” for any crop that the Government considers as remunerative for farmers and hence deserving of “support”.

- It is also the price that Government agencies pay whenever they procure the particular crop from the farmers.

- It is a way of protecting the farmers in India from the uncertainties of the markets as well as those of the natural kind.

- There is currently no statutory backing for these prices, nor any law mandating their enforcement.

Crops covered under MSP:

- At present, the Central Government sets MSP for 23 crops.

- These include:

- 7 cereals (bajra, wheat, maize, paddy barley, ragi and jowar);

- 5 pulses (tur, chana, masur, urad and moong);

- 7 oilseeds (safflower, mustard, niger seed, soyabean, groundnut, sesame and sunflower);

- 4 commercial crops (raw jute, cotton, copra and sugarcane).

How the Government decides on the MSP:

- The Government announces the MSP at the start of each cropping season (Rabi and Kharif).

- The MSP is decided after the Government exhaustively studies the recommendations made by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP).

- CACP is an attached office of the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare.

- These recommendations are based on a pre-fixed formulae. This includes the actual cost incurred, implicit family labour as well as the sort of fixed assets or rent paid by the farmers.

How can the Government provide legal guarantee for MSP:

- Primarily, there are two ways that the government can provide legal guarantee for MSP. Both have severe economic repercussions:

- First, the Government can declare MSP as the baseline price for the 23 crops in the market. It’ll be a mandate for private players to pay MSP rates, which may lead to price rise.

- Secondly, the Government itself can buy all 23 crops at MSP.

Consequences of according legal stature to MSP:

- A policy paper by NITI Aayog’s agricultural economist Ramesh Chand argues that price level that is not supported by demand and supply cannot be sustained through legal means.

- The paper noted that segments like horticulture, milk and fishery (where market intervention is nil or very little) showed 4-10% annual growth whereas the growth rate in cereals, where MSP and other interventions are quite high, remained at 1.1% after 2011-12.

- Higher procurement cost would mean increase in prices of food grains, leading to inflation, which would eventually affect the poor.

- There also lies practical difficulties in getting the private sector on board for buying at legally guaranteed MSP.

- The paper cited the example of sugarcane – where the support price (Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP)) is the statutory minimum price – and pointed out the accumulation of crores in arrears as private sugar mills could not find FRP for sugarcane matching with sugar prices.

Suggestions:

- Provide Direct Income Support

- MSP is a short-term solution. It is not a sustainable solution for all of Indian agriculture.

- Instead of arbitrarily fixing prices of goods in the market, the more effective way might be to provide direct income support to those who are poor — regardless of whether they are farmers or not.

- Investment Boost to Infrastructure

- Better irrigation facilities, easier access to credit, timely access to power, creating lots of warehouses, and ramping up of extension services including post-harvest marketing.

- It is when such facilities are provided — either free or at an accessible price point — that the Indian farmer would become less vulnerable.

- Eliminate Disguised Unemployment in Agriculture sector

- The solution to the economic distress of Indian farmers lies outside agriculture. It lies in boosting India’s industrial and services sectors.

- These are the two sectors that can absorb the excess labour that is engaged at present in extremely unremunerative farm activities and provide them with well-paying jobs.

- It is only when industries and services sectors grow rapidly for the next couple of decades that India’s farm distress will get alleviated.