Context:

- While Islamabad expressed the desire for a diplomatic handshake from across the border two weeks ago, it recently restated its request for third-party mediation in the Indus Water Treaty (IWT).

- This shows that the climate is not at all appropriate for the thawing of relations between the two nations, and it is still difficult to bridge the gap between words and deeds.

What is the Indus Water Treaty (IWT)?

- It is a water-distribution agreement between India and Pakistan that was mediated by the World Bank (WB) and signed in Karachi in 1960 by Jawaharlal Nehru, then the Indian PM, and Ayub Khan, then the president of Pakistan.

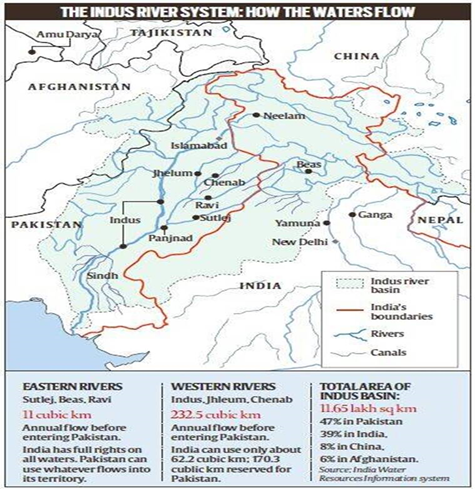

- The Treaty gives control over the waters of the three eastern rivers - the Beas, Ravi and Sutlej - to India (about 20% of the total water), while control over the waters of the three western rivers - the Indus, Chenab and Jhelum - to Pakistan (80%).

- India is granted unlimited non-consumptive usage of the western river waters for purposes like power generation and limited irrigation use.

- The dispute redressal mechanism provided under the IWT is a graded 3-level mechanism:

- Indus Commissioners

- Neutral Expert

- Court of Arbitration

Background in which Talks of Modifying IWT Started:

- In order to change the more than 60-year-old IWT that controls how the two nations share the waters of six rivers in the Indus system, India has sent Pakistan a notice via the Indus Commissioners.

- Article XII (3) of the IWT states that it may occasionally be altered by a treaty that has been properly approved.

- The notice comes as a result of Pakistan's continuous inaction in enforcing the IWT by repeatedly objecting to the development of hydroelectric projects on the Indian side.

- Two hydroelectric power projects, one on the Kishanganga river (a tributary of the Jhelum), and the other on the Chenab (Ratle), have been the subject of a prolonged controversy.

- In 2013, the Court of Arbitration gave a partial award on the Kishanganga Hydel Power Project (KHEP), upholding India’s right to divert water for the project.

- The Court refused to set a bar on the release of water, as demanded by Pakistan.

- However, it also restrained from making KHEP immune to environmental considerations.

- After the completion of the project, Pakistan objected to it again in 2014.

- Pakistan has also contested the Ratle project on grounds of design and violations of the IWT. The project was delayed but work resumed in 2019.

- Meanwhile, Pakistan asked the WB to establish a Court of Arbitration to look into the project.

- The WB in 2022 started a parallel process of simultaneously appointing a Neutral Expert and a Chair of the Court of Arbitration to resolve the dispute, which India claims presents both logistical and legal difficulties.

- India wanted a Neutral Expert to settle the conflict, whereas Pakistan wanted a Court of Arbitration.

Why Does India Want to Modify the IWT?

- Under Article 60 of the Vienna Convention on the Laws of the Treaties, a party can criticise an agreement and give notice of its intention to terminate it if the other party violates its fundamental provisions.

- India has adopted the moderate approach of not terminating but modifying the IWT.

- New Delhi claims that Islamabad has violated the dispute settlement mechanisms, as mandated by Articles 8 and 9 of the Treaty.

- Article 8 specifies the roles and responsibilities of the Permanent Indus Commission - a regular channel of communication for matters relating to the implementation of the Treaty.

- Article 9 offers a graded pathway (Neutral Expert, Court of Arbitration) to address any issue related to the implementation or interpretation of the IWT.

- As per India, Pakistan’s unilateral decision to approach the Permanent Court of Arbitration, bypassed the graded pathway.

What are the Concerns?

- Pakistan has shown a preference for third-party mediation, suggesting that this may be the most effective way to resolve the impasse in the two countries' relations.

- In India, Pakistan's opposition to the hydroelectric projects is viewed as a strategy to postpone them.

- These stances resemble diplomatic hedging - meaning that by pursuing two diametrically opposed strategies toward another state, balancing (preparing for the worst) and engagement, a state distributes its risk.

- They serve as a reminder that technically-negotiated agreements are just half of the solution and can cause transboundary rivers and their ecosystems to experience gradual strain over time.

Way Ahead:

- The two countries should use bilateral dispute settlement mechanisms to discuss the sustainable uses of water resources.

- Given the broad contours of the IWT - particularly Article 7 that talks about future cooperation - discussing and broadening transboundary governance issues in holistic terms could be the starting point for any potential diplomatic handshake.

Conclusion:

- Any analysis of international diplomacy would be incomplete if it looks only at legal aspects.

- The practice of diplomacy and the use of law for explaining and justifying government actions are equally important.