Why in News?

President Droupadi Murmu has invoked the Supreme Court’s advisory jurisdiction under Article 143(1) of the Constitution to seek its opinion on whether timelines can be mandated for the President and Governors to act on Bills passed by state legislatures.

This move came, following a Supreme Court ruling on April 8, where a two-judge Bench set a three-month deadline for the President to act on Bills reserved for her consideration.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Supreme Court’s Advisory Jurisdiction

- Supreme Court's Discretion in Responding to Presidential References

- Limits of Presidential Reference: No Tool for Overturning SC Judgments

- Presidential Reference Goes Beyond the April 8 Ruling

- Broader Context Behind the Presidential Reference

Supreme Court’s Advisory Jurisdiction

- The advisory jurisdiction is provided under Article 143 of the Constitution.

- It extends the Government of India Act, 1935 provision to include both questions of law and fact, including hypotheticals.

- The President may refer a question that "has arisen, or is likely to arise",

- It must be of public importance and require the Supreme Court’s opinion.

- Usage History

- This power has been used at least 15 times since 1950.

Supreme Court's Discretion in Responding to Presidential References

- Discretionary Nature of Article 143(1)

- Article 143(1) states the Supreme Court “may” report its opinion, indicating that the Court has the discretion to decline a reference.

- The SC has declined at least two such references in the past.

- Notable Cases Where the SC Declined

- 1993 – Ram Janma Bhumi-Babri Masjid Reference

- President Shankar Dayal Sharma asked whether a Hindu temple or religious structure existed before the Babri Masjid.

- The SC unanimously declined to answer as the matter was already sub judice in a civil suit.

- 1982 – Jammu & Kashmir Resettlement Law Reference

- President Giani Zail Singh referred the constitutionality of a Bill on the resettlement of people who migrated to Pakistan.

- The SC did not return an opinion as:

- The Bill was enacted after being passed a second time and assented to by the Governor.

- Petitions challenging the law were already pending before the Court.

- Since advisory opinions are not binding, the Court would have to decide the issue afresh in regular litigation.

- Key Insight

- The advisory opinion under Article 143 is non-binding and not a substitute for judicial review.

- The Court may refuse to answer if the issue is already in court, violates constitutional principles, or becomes irrelevant.

Limits of Presidential Reference: No Tool for Overturning SC Judgments

- Presidential Reference Cannot Reverse Judicial Decisions

- In its 1991 Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal opinion, the Supreme Court clarified that Article 143 is not meant for reviewing or overturning the Court’s prior judgments.

- Once the SC has given an authoritative ruling on a legal issue, it cannot be reconsidered via a presidential reference.

- Advisory Jurisdiction Not an Appeal Mechanism

- The Court stated that using Article 143 to revisit a settled decision would mean sitting in appeal over its own ruling, which is impermissible even in regular judicial processes.

- The President cannot confer appellate powers on the SC through a reference.

- Available Legal Remedies for the Government

- The government can still file a review petition against the April 8 ruling.

- If the review is dismissed, it may file a curative petition—a rare legal remedy to correct gross miscarriage of justice.

- Possibility of Reconsideration by Larger Bench

- Since the April 8 ruling was delivered by a two-judge Bench, and similar matters from states like Kerala and Punjab are pending, a larger Constitution Bench may eventually examine the issue, providing scope for a fresh judicial interpretation.

Presidential Reference Goes Beyond the April 8 Ruling

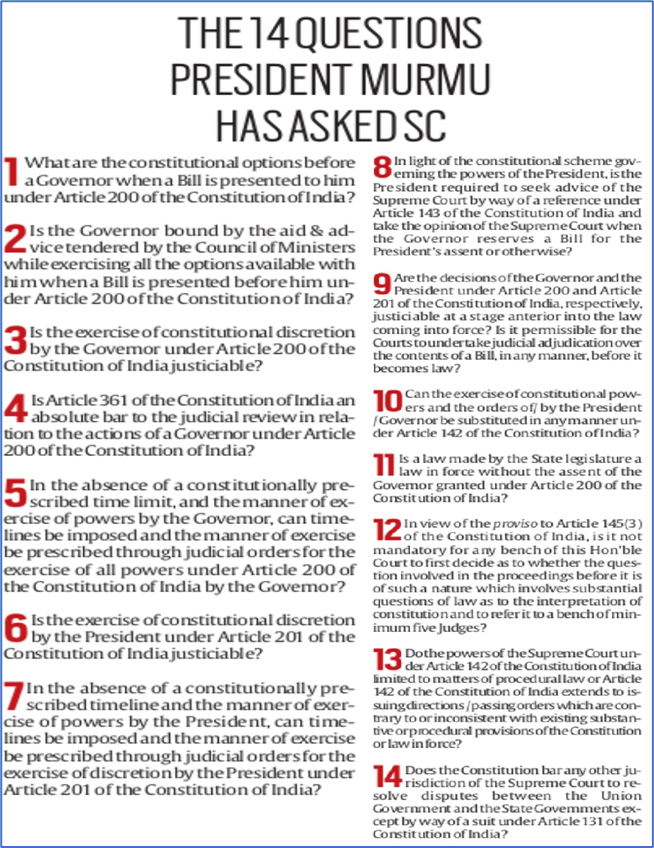

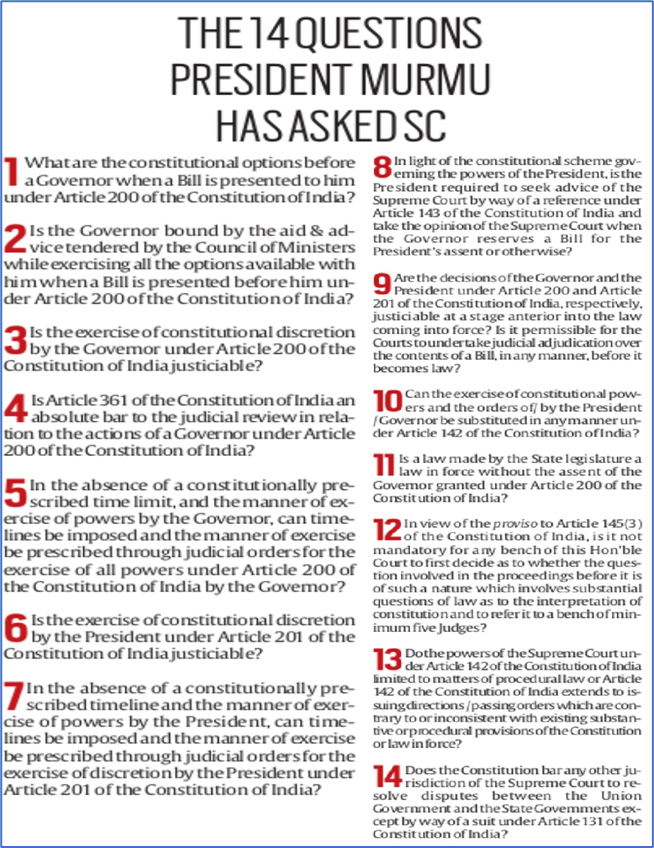

- Broader Scope: 14 Questions of Law Raised

- The presidential reference includes 14 legal questions, many of which stem from the April 8 Supreme Court ruling, but it is not limited to that verdict alone.

- The final questions raise deeper constitutional issues about the Supreme Court’s discretionary powers and jurisdiction.

- Questioning Bench Composition for Key Matters (Q12)

- Question 12 asks whether the SC must first determine if a case involves a “substantial question of law” or requires constitutional interpretation, in which case only a larger Bench should hear it.

- This effectively challenges whether smaller Benches can decide such weighty constitutional issues.

- Use of Article 142 – Power to Do Complete Justice (Q13)

- Question 13 focuses on the scope and limitations of Article 142, under which the SC can exercise its discretionary powers to ensure “complete justice”.

- The reference seeks clarity on the boundaries of this broad power.

- Centre–State Disputes and Article 131 (Q14)

- The final question pertains to Centre–state disputes and asks the SC to define the jurisdictional limits of courts in such cases.

- Article 131 grants the Supreme Court exclusive original jurisdiction, but the reference questions how broadly this should be interpreted.

Broader Context Behind the Presidential Reference

- Centre vs Opposition-ruled States: The Governor’s Role

- The dispute stems from ongoing power struggles between the Centre and Opposition-ruled states.

- Governors, appointed by the Centre, have been accused of stalling state legislation by withholding or delaying assent to Bills passed by elected Assemblies.

- In the R N Ravi case, the Tamil Nadu Governor withheld assent to 10 Bills, later referring them to the President.

- April 8 SC Judgment: Extending Judicial Oversight

- The SC not only addressed Governor inaction but also set a three-month deadline for the President to act on such Bills.

- The Court further allowed states to seek a writ of mandamus against the President, compelling a decision if timelines are not followed.

- This move was seen by the government as an encroachment on executive authority.