Context

- India recently banned the exports of broken rice and imposed a 20 per cent duty on the exports of various grades of rice amid high cereal inflation and uncertainties with respect to domestic supply.

- This decision to curb rice exports has, unfortunately, been taken when global food prices are already rising and have heightened food security anxieties across the global market as many developing countries depend on Indian rice.

Statistics

- Production: Rice is India’s largest agricultural crop accounting for over 40% of the total foodgrain output.

- Consumption: India, the world’s biggest rice consumer after China

- Export valuation: India is also being the world’s biggest exporter as a record 212.10 lakh metric tonnes (LMT)/ 21.21 mt valued at $9.66 billion got shipped out during the fiscal ending March 2022.

- Global trade share: India exports rice to more than 130 countries, constituting around 40 per cent of the global rice trade.

About Broken Rice

- Broken rice is fragments of rice grains, broken in the field, during drying, during transport, or during milling. Mechanical separators are used to separate the broken grains from the whole grains and sort them by size.

- Broken rice is fragmented, not defective hence there is nothing wrong with it.

Reasons for recent rice ban

- Price rise: As per Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, the price of rice which was around Rs 15-16 per kg as on 1st January 2022 has increased to Rs 22 per kg in September 2022.

- Rise in export share: As per government, the broken rice exports have increased 42 times to 21.31 lakh metric tonnes (LMT) during April-August 2022 as compared to 0.51 LMT during the corresponding period of 2019, which is absolutely abnormal.

- Also the broken rice export figure for the full financial year shows an increase of more than 300 per cent from 12.21 lakh metric tonnes in 2018-19 to 38.90 LMT in 2021-22.

- China-the top buyer: China has emerged as the top buyer of Indian rice during the pandemic, importing 16.34 LMT or 7.7 per cent of India’s total rice export of 212.10 LMT in 2021-22.

- Out of this total rice import by China from India nearly 97 per cent, or 15.76 LMT, was broken rice.

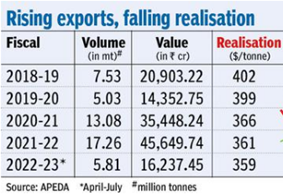

- Falling realisation: The per tonne realisation from rice exports declined 11 per cent from $402 in 2018-19 to $359 during the April-July period of the current fiscal (2022-23).

- Decreased harvest: The total rice sowing during the 2022 kharif season has been so far about 20 lakh hectare less as compared to the corresponding figure of the last year, which may lead to fall in rice production by 10 million tonnes and rise in rice prices.

- The primary reason for the decline in the sown area could be attributed to the slow advancement of the monsoon in the month of June and its uneven spread in July in some growing key regions in the country.

- Policy exigency: Though the stocks for rice was comfortable, but given the political pressure to continue the free-food grain scheme under Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana beyond September has convinced the export ban.

- Paucity in Domestic Market: The demand for broken rice has increased within the country of-late for poultry feed or for ethanol for which broken rice or damaged foodgrains are being used.

Significance of the move

- Crucial supplier: India’s rice exports in 2021 was more than the combined shipments of the world’s next four biggest exporters of the grain, i.e. Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan, and the United States.

- Critical impact: The world rice market is thin, given that 90 per cent of production is consumed domestically.

- As a result, any small change in exports and imports has an enormous impact on prices, especially if it leads to panic buying of food grains by rich countries.

- Fuel inflation: Any reduction in its shipments would fuel food inflation.

- Impact on small economies: India’s export restrictions will adversely affect several low-income and low-middle-income countries like Bangladesh, Senegal, Nepal and Benin, which are among the largest importers of Indian rice.

- Undesirable outcomes for India: The export uncertainties will affect the credibility of Indian exporters, create a disincentive for future exports, and will enable buyers to shift towards other major rice-exporting countries.

- Impact on Indian farmers: Though Indian farmers in general lack market access, and hence do not take advantage of high market prices, the fall in prices may adversely affect a section of farmers who hope to get a better price for their produce through exports.

- Also, the exporters who face the burden of the unfeasibility of exports may pass it on to farmers in the form of lower prices during procurement.

Rice and groundwater vulnerability

- Over-reliance on groundwater: In India, around 49 per cent of rice cultivation depends on groundwater which is depleting rapidly.

- Data: As per the latest data available from the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), agricultural water withdrawal as a percentage of total available renewable water resources has increased from 26.7 per cent in 1993 to 36 per cent in 2022.

- Comparison with other rice exporting nations: The other major exporters of rice, such as Thailand and Vietnam, have better per capita water availability in comparison to India.

- In context of major rice importing countries, out of 133 countries in which India has positive net rice exports, only 39 countries have relatively lower per capita renewable water resources.

- Also, out of these 39 countries, 12 countries are high-income countries with the ability to buy food at a higher price.

- Contingency: Similarly, the total per capita renewable water resources have also declined from 1,909 cubic meters to 1,412 cubic meters during this period.

- The water-intensive nature of rice cultivation, along with frequent export restrictions will adversely affect the long-run sustainability of rice production.

- Virtual water export: Rice exports are leading to an indirect export of water to other countries, a phenomenon known as virtual water trade (VWT).

- India’s rice yield is also lower than the world average. India’s yield is better than Thailand and Pakistan but worse than Vietnam, China and the US.

- Skewed procurement: The Minimum Support Prices (MSPs) regime favours mainly rice and wheat and procurement is skewed towards selected northern states such as Punjab and Haryana where water availability is lower than in several other states.

Way forward

- Judicious water utilization: The input requirements in the form of wider adoption of water-saving practices such as the system of rice intensification (SRI) need to be undertaken.

- Otherwise, the cost of cultivation will increase and production will become unsustainable.

- Higher support prices: The cost of cultivation in India is also increasing, and hence there will be a need for a higher MSP to make production remunerative and a policy re-think on price support-backed food security mechanism.

- Minimum export price: Minimum export price can be announced to prevent any under-invoicing.

- Scrutiny: Regular checks should be undertaken to ensure premium non-Basmati rice that is sold at over $650 a tonne does not get shipped as Basmati rice to escape the 20 per cent tax or other types of rice are not mixed with Basmati and shipped out to evade the tax.