Why in News?

- The current government will end its second term with overall public debt in excess of 80% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- What Government/ Public Debt Entails?

- Data Related to the Public Debt in India

- Why has India’s Public Debt Spiraled?

- Scenario in Other Economies

- Ways to Deal with the High Govt Debt

What Government/ Public Debt Entails?

- Government debt is basically the outstanding domestic and foreign loans (plus other liabilities) raised by the Centre and states (to meet its development expenditure) - on which they have to pay interest and the principal amounts borrowed.

- It is measured by the debt-to-GDP ratio, which is the ratio between a country's government debt (measured in units of currency) and its gross domestic product (GDP) (measured in units of currency per year).

- As per the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM)Act 2003,

- The general government debt (Centre + states) was supposed to be brought down to 60% of GDP by 2024-25.

- The Centre’s own total outstanding liabilities were not to exceed 40% within that time schedule.

Data Related to the Public Debt in India:

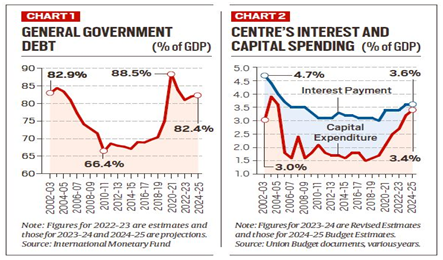

- According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), general government debt - the combined domestic and external liabilities of both the Centre and the states - touched 84.4% of GDP in 2003-04.

- That ratio fell to a low of 66.4% in 2010-11 and rose gradually to 67.7% in 2013-14 and 70.4% in 2018-19.

- The debt-GDP ratio soars to 75% in 2019-20 and peaks at 88.5% in 2020-21, before easing to 83.8% and 81% in the following two fiscal years (April-March).

- In absolute terms, the Centre’s total liabilities have more than doubled from Rs 90.84 lakh crore to Rs 183.67 lakh crore between 2018-19 and 2024-25.

- The IMF has projected the ratio at 82% in the current fiscal and 82.4% for 2024-25, which is still close to the high levels of the early 2000s.

Why has India’s Public Debt Spiraled?

- The most obvious reason is the Covid-induced disruptions that forced governments to borrow more - to fund additional public health and social safety net expenditure requirements - amid a drying up of revenues.

- The Indian government, apart from spending more on income and consumption support schemes, also stepped-up public investments in roads, railways and other infrastructure.

- The Centre’s capital expenditure dropped from 3.9% to 1.5% of GDP between 2003-04 and 2017-18.

- It revived significantly thereafter to reach 3.2% in 2023-24 and 3.4% in the Interim Budget for 2024-25.

- All these widened the deficits and only added to debt. For example, the Centre’s fiscal deficit alone increased from 3.4% of GDP in 2018-19 to 4.6% in 2019-20, 9.2% in 2020-21 and 6.8% in 2021-22.

Scenario in Other Economies:

- India was no exception though. Most countries sought to mitigate the impact of the pandemic through fiscal stimulus and relief programmes.

- General government debt climbed from 108.7% of GDP in 2019 to 133.5% in 2020 and 121.4% in 2022 for the US; from 97.4% to 115.1% and 111.7% for France; and 60.4% to 70.1% and 77.1% for China during these years.

Ways to Deal with the High Govt Debt:

- The FRBM Act envisaged limiting the Centre’s gross fiscal deficit to 3% of GDP by 2020-21.

- The Union Budget 2021-22, announced to attain a fiscal deficit-to-GDP ratio of “below 4.5%” by 2025-26.

- But given the high post-pandemic starting points in 2020-21 and 2021-22, the deficit ratios of “below 4.5%” by 2025-26 will be difficult to achieve.

- There are two other routes as well for bringing the latter down. That would involve what one may call the denominator effect.

- Government debt and fiscal deficits are usually quoted as ratios to GDP at current market prices.

- This means, high nominal GDP growth - the denominator rising faster than the numerator - can go some way in solving the government’s debt problem.

- GDP growth can be driven by both increases in real output and inflation.

- This actually happened during 2003-04 to 2010-11, when India witnessed an average annual GDP growth of 7.4% in real and 15%-plus in nominal terms after adding inflation.

- India probably needs a combination of both fiscal consolidation and growth (from output more than inflation) to deal with its current debt woes, which are also a result of Covid.