In News:

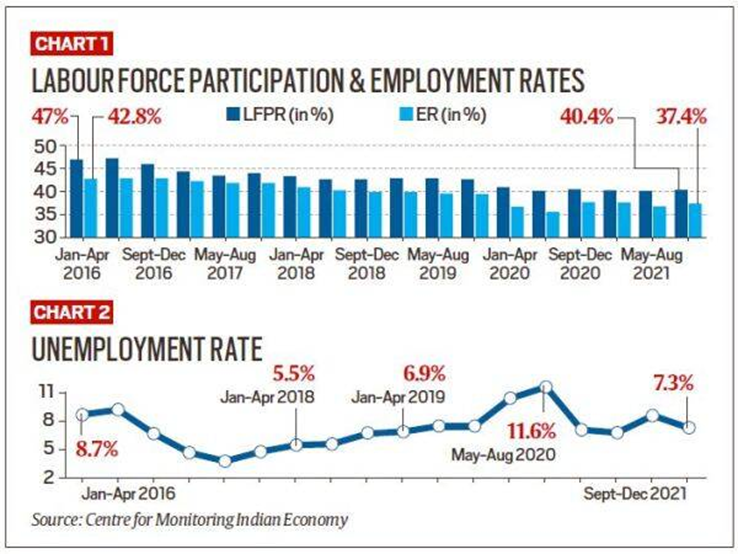

- Data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) shows that India’s labour force participation rate (LFPR) has fallen to just 40% from an already low 47% in 2016.

- This suggests not only that more than half of India’s population in the working-age group (15 years and older) is deciding to sit out of the job market, but also that this proportion of people is increasing.

What’s in today’s article:

- About LFPR (Meaning, Formula, Significance, Under-reporting, Why is it low, etc.)

- Reasons for low female LFPR in India

- Central government’s response to CMIE report

What is LFPR?

- According to the CMIE, the labour force consists of persons who are of age 15 years or older, and belong to either of the following two categories:

- Employed

- Unemployed and are willing to work and are actively looking for a job

- There is a crucial commonality between the two categories — they both have people “demanding” jobs. This demand is what Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) refers to.

- While those in category 1 succeed in getting a job, those in category 2 fail to do so.

- Essentially, LFPR is the number of people ages 15 and older who are employed or actively seeking employment, divided by the total non-institutionalized, civilian working-age population.

- LFPR represents the demand for jobs in an economy.

- On the other hand, Unemployment Rate (UER), which is routinely quoted in the news, is nothing but the number of unemployed (category 2) as a proportion of the labour force.

Significance of LFPR in India:

- Typically, it is expected that the LFPR will remain largely stable.

- As such, any analysis of unemployment in an economy can be done just by looking at the UER. But, in India, the LFPR is not only lower than in the rest of the world but also falling.

- This, in turn, affects the UER because LFPR is the base (the denominator) on which UER is calculated.

- The world over, LFPR is around 60%. In India, it has been sliding over the last 10 years and has shrunk from 47% in 2016 to just 40% as of December 2021.

- This shrinkage implies that merely looking at UER will under-report the stress of unemployment in India.

How is it under-reported?

- Imagine that there are just 100 people in the working-age group but only 60 ask for jobs — that is, the LFPR is 60% — and of these 60 people, 6 did not get a job.

- This would imply a UER of 10%.

- Now imagine a scenario when the LFPR has fallen to 40% and, as such, only 40 people are demanding work. And of these 40, only 2 people fail to get a job.

- The UER would have fallen to 5% and it might appear that the economy is doing better on the jobs front but the truth is starkly different.

- The truth is that beyond the 2 who are unemployed, a total of 20 people have stopped demanding work. Typically, this happens when people in the working-age get disheartened from not finding work.

- In India’s case, every time the LFPR falls, the UER also falls — because fewer people are now demanding jobs — giving the incorrect impression to policymakers that the situation has improved.

What is the correct way to assess India’s Unemployment Stress?

- When LFPR is falling as steadily and as sharply as it has done in India’s case, it is better to track another variable: the Employment Rate (ER).

- The ER refers to the total number of employed people as a percentage of the working-age population.

- By using the working-age population as the base and looking at the number of people with jobs (instead of those without them), the ER captures the fall in LFPR to better represent the stress in the labour market.

- In December 2021, India had 107.9 crore people in the working age group and of these, only 40.4 crore had a job (an ER of 37.4%).

- Compare this with December 2016 when India had 95.9 crore in the working-age group and 41.2 crore with jobs (ER 43%).

- In five years, while the total working-age population has gone up by 12 crore, the number of people with jobs has gone down by 80 lakh.

Why is India’s LFPR Low?

- The main reason for India’s LFPR being low is the abysmally low level of female LFPR.

- According to CMIE data, as of December 2021, while the male LFPR was 67.4%, the female LFPR was as low as 9.4%.

Reasons for the fall in women’s LFPR in India:

- Occupational Segregation:

- Between 1977 and 2017, India’s economy witnessed a surge in the contribution of services (39 percent to 53 percent) and industry (33 percent to 27 percent) to GDP.

- The proportion of rural men employed in agriculture fell from 80.6 percent to 53.2 percent, but rural women only decreased from 88.1 percent to 71.7 percent.

- Between 1994-2010, women received less than 19 percent of new employment opportunities generated in India’s 10 fastest-growing occupations.

- Increased Mechanisation:

- In agriculture, as the use of seed drillers, harvesters, threshers and husking equipment increased, men displaced women.

- In textiles, power looms, button stitching machines and textile machinery phased out women’s labour.

- Nearly 12 million Indian women could lose their jobs by 2030 owing to automation, according to a McKinsey Global Institute report.

- Income Effect:

- With increasing household incomes, especially over the last three decades, the need for a “second income” reduced.

- Consequently, families withdrew women from labour as a signal of prosperity.

- This “income effect” can explain approximately 9 percent of the total decline in the female labour force participation rate between 2005 to 2010.

- Gender gaps in Higher Education & Skill Training:

- Tertiary-level female enrolment rose from 2 percent in 1971 to only 30 percent in 2019 (World Bank data).

- As of 2018-19, only 2 percent of working-age women received formal vocational training, of which 47 percent did not join the labour force (NSSO, 2018-19).

- Consequently, women holds only 17 percent of cloud computing, 20 percent of engineering, and 24 percent of data/artificial intelligence jobs (WEF, 2020).

- Social Norms:

- Unpaid care work continues to be a women’s responsibility, with women spending on average five hours per day on domestic work, vs. 30 minutes for men (NSSO, 2019).

- Women face inordinate mobility restrictions such that only 54 percent can go to a nearby market alone (NFHS, 2015-16).

- Women regularly sacrifice wages, career progression, and education opportunities to meet family responsibilities, safety considerations, and other restrictions.

Way Forward:

- To chart a gender-sensitive socio-economic recovery post-COVID-19, the government, the private sector, media, and the social sector need to work together to:

- Improve working conditions,

- Reduce wage gaps,

- Increase opportunities for women across sectors, and change mindsets.

- State governments may establish gender-based employment targets for urban public works.

- Central or state governments can consider introducing wage subsidies to incentivise hiring women in micro, small and medium enterprises.

Government’s Response to CMIE’s Findings:

- Responding to the report, the Union Labour and Employment Ministry said it was “factually incorrect” to infer that half the working age population had dropped out of the labour force as a large proportion was pursuing education or engaged in unpaid activities such as caregiving.

- According to the Education Ministry, more than 10 crore people were enrolled in secondary, higher secondary, higher or technical education in 2019-2020 and 49% of that was women.

- Fall in Unemployment Rate:

- It added that the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation’s Periodic Labour Force Survey had shown an increase in the labour force participation rate.

- The LFPR increased from 49.8% in 2017-2018 to 53.5% in 2019-2020 and a decrease of unemployment rate from 6% to 4.8%.

- It said the Economic Survey 2021-2022 had indicated an increase of 4.75 crore in employment in 2019-2020 from 2018-2019.