Oct. 31, 2025

Mains Article

31 Oct 2025

Why in the News?

- The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) has announced plans to use data from the Annual Survey of Unincorporated Sector Enterprises and the Periodic Labour Force Survey to develop a District Domestic Product (DDP) framework for more accurate, district-level economic estimation.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Statistical Ecosystem (ASUSE & PLFS Surveys, Purpose & Methodology for DDP, Significance of DDP, Challenges & Way Forward)

MoSPI to Use ASUSE and PLFS Surveys for Accurate District Domestic Product Estimation

- The MoSPI has announced a significant step toward improving India’s statistical architecture by integrating two major datasets to calculate the District Domestic Product:

- The Annual Survey of Unincorporated Sector Enterprises (ASUSE) and

- The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS)

- This initiative aims to provide more accurate, district-level economic data and empower states to make evidence-based policy decisions.

Context: Strengthening India’s Statistical Ecosystem

- At present, India’s national and state-level GDP data often fail to capture regional variations within districts.

- Most District Domestic Product (DDP) estimates rely on top-down allocation methods, proportionately distributing state GDP based on outdated demographic indicators like population.

- This approach has long been criticised by experts who highlighted that the current method results in “near-identical growth rates for districts,” thus masking true inter-district disparities.

- Recognising this data gap, MoSPI announced that beginning January 2025, the ministry will work with state governments to introduce a bottom-up estimation model using detailed datasets from ASUSE and PLFS.

About ASUSE and PLFS

- Annual Survey of Unincorporated Sector Enterprises (ASUSE)

- ASUSE captures detailed data on India’s vast unincorporated non-agricultural sector, covering manufacturing, trade, and services enterprises, including households, micro, and small units.

- This survey provides insights into the economic and operational characteristics of establishments that often remain outside the formal sector’s purview.

- Earlier released annually, ASUSE now provides quarterly data for enhanced frequency and granularity. It serves as a critical input for understanding local enterprise activity, investment, and value addition patterns.

- Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS)

- PLFS is conducted by the National Statistical Office (NSO) to measure employment, unemployment, and labor market participation across rural and urban areas.

- The survey is now conducted monthly, capturing dynamic trends in workforce participation, earnings, and occupational structures.

- By combining ASUSE (enterprise data) and PLFS (labour data), the government aims to create a comprehensive database of district-level economic activities, bridging the enterprise and employment dimensions of local economies.

Purpose and Methodology for Estimating DDP

- The integration of ASUSE and PLFS will allow policymakers to capture real economic activity at the district level rather than relying on extrapolated state averages.

- Key features of the initiative include:

- Bottom-up estimation: District-level data will be aggregated upward to form state and national accounts, reversing the current top-down allocation model.

- Dual-sector coverage: The approach accounts for both enterprise activity (ASUSE) and labour participation (PLFS), ensuring holistic measurement of economic output.

- Policy collaboration: MoSPI is working closely with state governments to align data collection frameworks with local administrative and planning needs.

- Inclusion of informal sector: Since unincorporated enterprises and household-level activities form a large share of India’s economy, the new methodology ensures that informal sector output is adequately represented.

Complementary Statistical Initiatives

- The effort to refine DDP estimation is part of MoSPI’s broader agenda to modernise India’s statistical system. Several related initiatives are underway:

- Annual Survey of Service Sector Enterprises (ASSSE): To be launched in January 2026, this will capture the dynamics of incorporated services such as IT, financial services, and logistics.

- National Household Income Survey (NHIS): Scheduled for February 2026, it aims to measure income distribution, wealth, and inequality, complementing consumption and employment data.

- Expanded data accessibility: MoSPI has identified over 250 datasets for improved public access, including data from GST, E-Vahan, and trade statistics, to enrich national accounts and research capacity.

Significance of District Domestic Product (DDP)

- The DDP represents the gross value added (GVA) within a district’s geographical boundaries.

- It serves as a microeconomic counterpart to the state’s Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP).

- An accurate DDP framework can enable:

- Targeted policy interventions by identifying lagging districts.

- Evidence-based fiscal planning at local levels.

- Better assessment of regional inequality and employment trends.

- Alignment with decentralised planning under India’s federal structure.

- The move also aligns with the government’s vision of Viksit Bharat @2047, where data-driven governance is seen as central to inclusive development.

Challenges and the Way Forward

- While the initiative is promising, implementing district-level GDP estimation faces several challenges:

- Data reliability: Unincorporated sector data can be difficult to capture consistently.

- Coordination with states: States vary in statistical capacity and infrastructure.

- Avoiding double-counting: Integrating enterprise and labour datasets requires precise harmonisation.

- Nonetheless, experts consider this reform a crucial step toward improving the granularity, reliability, and timeliness of economic data in India.

- With states like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka already experimenting with DDP frameworks, MoSPI’s bottom-up model may soon standardise district-level measurement across the country.

Mains Article

31 Oct 2025

Why in News?

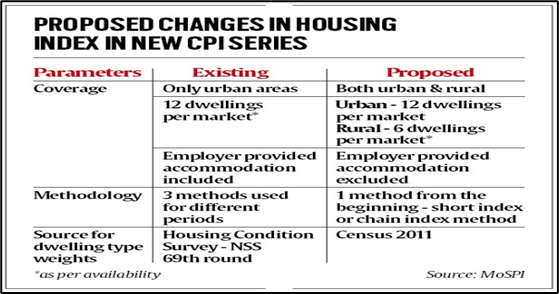

- The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) has proposed key methodological reforms in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), specifically in the compilation of the housing index.

- These reforms aim to make inflation measurement more accurate, representative, and transparent, reflecting post-pandemic changes in rental markets and including rural housing data for the first time.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Background - CPI and Housing Index

- Proposed Methodological Changes

- Inclusion of Rural Sector through HCES 2023-24

- Transparency and Consultation Process

- Way Forward

- Conclusion

Background - CPI and Housing Index:

- The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is India’s main measure of retail inflation.

- The MoSPI is revising the CPI base year to 2024 from 2012, with item weights based on the 2023-24 Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES).

- Currently, housing data is collected biannually and only for urban areas.

- The weight of housing in the CPI basket is 21.67% for urban areas and 10.07% at the all-India level.

- According to data released last month, housing inflation accelerated to 3.98% in September from 3.09% in August. Overall, India's retail inflation eased to 1.5% from 2.1% over the same period.

- Economists have long criticized the inclusion of employer-provided dwellings and use of House Rent Allowance (HRA) as a rent proxy.

Proposed Methodological Changes:

- Monthly rent data collection:

- Rent data will be collected monthly instead of every six months.

- Coverage expanded to both rural and urban areas, marking a major shift.

- The dwelling type weight will be based on Census 2011.

- Exclusion of employer-provided housing: Government and employer-provided accommodations will be excluded to avoid distortions since they don’t reflect market transactions.

- Expanded sample and IMF guidance:

- Rent data to be collected from all selected dwellings every month (earlier one-sixth sample).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF) technical experts recommended refining India’s panel approach to improve representativeness.

- The revised formula ensures “like-for-like” comparison and avoids downward bias in rent index computation.

Inclusion of Rural Sector through HCES 2023-24:

- The HCES 2023-24 has, for the first time, captured rural house rent and imputed rent for owner-occupied dwellings.

- This enables compilation of a rural housing index, absent in the HCES 2011-12 series.

- The new series will therefore represent comprehensive national housing dynamics.

Transparency and Consultation Process:

- MoSPI released the third discussion paper as part of its base revision exercise of the CPI. Previous papers focused on ‘Treatment of Free Public Distribution System (PDS) Items in CPI Compilation’.

- The Ministry plans to hold data conferences and stakeholder consultations to enhance transparency and inclusiveness.

- Feedback on the housing index changes has been invited till November 20, 2025.

Way Forward:

- The proposed CPI revision will align India’s methodology with global statistical best practices.

- Continuous data collection from rural and urban areas will improve the robustness of inflation measurement.

- Exclusion of non-market housing will enhance accuracy in assessing true inflationary pressures.

- The exercise will also help policy-makers, RBI, and households better understand the impact of housing costs on inflation and real income.

Conclusion:

- The overhaul of the housing index methodology marks a significant reform in India’s CPI framework.

- By integrating monthly, all-India rent data and removing distortionary elements, MoSPI aims to create a more representative and credible inflation index.

- This reform is crucial in the context of post-pandemic rental surges, rural-urban housing disparity, and the need for data-driven economic policymaking in a rapidly evolving economy.

Mains Article

31 Oct 2025

Context

- India stands on the threshold of a paradigm shift in education, poised to introduce Artificial Intelligence (AI) into classrooms as early as Class 3 starting in 2026–27.

- This transformative move, aligned with the National Education Policy 2020, reflects a bold ambition: to prepare future generations for an AI-powered global economy.

- Also, it is important to ensure the nation remains competitive in an era defined by automation and digital innovation.

AI as a Catalyst for Educational Reform

- The integration of AI into the K-12 system is not merely a technological upgrade, it represents a reimagining of how learning occurs.

- AI-driven platforms offer personalised learning pathways, adjusting instruction based on a student’s pace, strengths, and struggles.

- Such adaptive systems can democratise education by supporting learners with diverse needs, addressing regional language barriers, and creating more inclusive environments, a particularly critical objective in India’s vast socio-educational landscape.

Teachers at the Core of Transformation

- However, technology alone cannot revolutionise education. With over one crore teachers nationwide, the success of this initiative hinges on capacity-building and continuous professional development.

- Pilot programmes have already trained thousands of educators, equipping them with AI tools for lesson planning and resource design.

- Yet, the magnitude of upskilling required raises crucial questions: Are teachers adequately prepared to transition from traditional instructors to AI-guided mentors?

- The answer will determine the pace and depth of this reform.

Balancing Technology with Human Insight

- Despite the power of AI, human educators remain irreplaceable.

- AI can automate administrative tasks like grading and attendance, offering teachers more time for creative instruction, emotional support, and personalised interaction, areas where machines cannot replicate human empathy and intuition.

- In this hybrid model, teachers evolve into facilitators of higher-order thinking, supported rather than overshadowed by technology.

The Future Workforce: Promise and Challenge

- The integration of AI into education also reflects broader shifts in labour markets.

- While projections suggest millions of jobs may be disrupted, AI could generate even more employment opportunities by 2030.

- Equipping students with AI literacy from early grades ensures they are prepared not only to navigate but to thrive in a rapidly evolving digital economy.

- Yet, this requires not only technical skills but resilience, creativity, and ethical awareness.

Bridging the Inequality Gap

- One of the most compelling promises of AI in education is its potential to expand access and equity.

- From generative AI tutors to multilingual learning tools, technology could help close achievement gaps and extend quality education beyond urban hubs.

- However, this promise is contingent upon addressing digital infrastructure disparities and ensuring affordability, without which the AI revolution risks widening existing inequalities instead of reducing them.

Conclusion

- India’s initiative to embed AI into school education marks a watershed moment for its learning ecosystem.

- It embodies aspiration, innovation, and foresight, yet also raises critical questions about readiness, inclusivity, and ethical implementation.

- The future of India’s education system will depend on thoughtful policy, teacher empowerment, and equitable access.

- As the nation navigates this transformation, one truth stands clear: AI is not merely a tool but a catalyst, reshaping the very contours of learning and unlocking possibilities for a generation preparing to shape the AI-driven world.

Mains Article

31 Oct 2025

Why in news?

At the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in South Korea, US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping met for the first time since Trump’s return to office.

Trump announced that China agreed to maintain global exports of rare earth minerals under a one-year deal, calling it a “worldwide solution.” He said this would remove supply worries for industries dependent on these materials.

Additionally, the US will reduce tariffs on China—cutting the penalty on fentanyl-related trade from 20% to 10%, bringing the overall tariff rate down from 57% to 47%.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Key Highlights of the Xi-Trump Meeting

- Implication for India in the G-2 world

Key Highlights of the Xi-Trump Meeting

- The meeting was its carefully managed optics. Unlike his usual confrontational style, President Trump adopted a polite and diplomatic tone, showing awareness of China’s global influence.

- Interestingly, China did not immediately release an official account of the meeting, highlighting its cautious approach.

- Trump’s Recognition of China’s Power

- Trump referred to the meeting as “G-2”, equating the US–China relationship to elite global groupings like the G-7 and G-20.

- This was seen as a symbolic recognition of China’s global power, something no previous US president had done publicly — a clear diplomatic win for Beijing.

- Controlled Diplomacy Over Confrontation

- Both leaders showed mutual deference and restraint, a departure from Trump’s usual brashness.

- Their conduct reflected a shared understanding of the delicate balance between the world’s two largest economies and the global impact of their relationship.

- Deal on Rare Earth Exports

- The key takeaway from the Trump–Xi meeting was about rare earth exports.

- President Trump announced that China had agreed to continue exporting rare earth minerals for one year — a relief for global industries that depend on them.

- In return for China’s cooperation, Trump cut tariffs on Chinese goods by 10%, lowering total US tariffs from 57% to 47%.

- This move was meant to ease pressure on Chinese businesses and encourage Beijing to compromise.

- While the agreement eased tensions, it only postponed the core issue — China still dominates the rare earth supply chain.

- The deal gives the US and its allies more time to diversify sources and reduce dependency on China.

Implication for India in the G-2 world

- In his first term (2017), Trump took a hard stance on China, calling it a strategic rival, strengthening alliances, and supporting frameworks like the Quad and Indo-Pacific strategy, where India played a central role.

- Now, in his second term, Trump’s approach is commercial, focusing on trade deals and domestic investments, even pressuring allies like Japan and South Korea to invest heavily in the US.

- After the meeting, US President left behind a sense of uncertainty about America’s future with China — the world’s two largest powers.

- Calling his meeting with Xi Jinping a “G-2” summit, Trump sparked concern among allies that the US is leaning toward a China-first, business-focused policy.

- Implications for India and the Region

- For India, the message was clear: the US focus remains on managing China.

- The question now is whether Trump prefers working with allies like India, Japan, and Australia (under the Quad) or handling China alone.

- For India and other Asian nations, this marks a new phase in US–China relations — a mix of competition and cooperation.

- Trade Disadvantage for India

- After Trump reduced tariffs on China to 47%, India now has the highest tariff rate at 50%, putting it at a trade disadvantage.

- This makes a US–India trade deal more urgent.

- Until then, a US rival (China) enjoys better trade terms than a US partner (India).

- India’s Strategic Path Forward

- As Trump’s trade-driven strategy reshapes the region, India must rethink its assumptions about both American intent and Chinese ambition, while identifying space for its own strategic autonomy.

- For India, the challenge is to navigate this shifting US–China balance with agility.

- Delhi must:

- Engage the US where interests align,

- Explore economic opportunities with China where possible, and

- Deepen partnerships with Asia and Europe to strengthen its independent position.

Mains Article

31 Oct 2025

Why in news?

India has consistently opposed unilateral economic sanctions, but has often complied with US-imposed restrictions to avoid fallout.

In the past, Indian refiners stopped importing oil from Iran and Venezuela after the US sanctioned those countries. Now, with new US sanctions on Russian oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil, a similar situation looms.

India avoids dealing with sanctioned entities mainly due to the risk of US secondary sanctions, which could penalize third-party countries or companies doing business with the targeted nations.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Understanding Secondary Sanctions

- Why Countries Fear US Secondary Sanctions

- Why US Sanctions Matter for India

Understanding Secondary Sanctions

- Secondary sanctions extend beyond the direct targets of US restrictions.

- Primary sanctions stop American citizens and companies from dealing with blacklisted entities (like Rosneft and Lukoil).

- On the other hand, secondary sanctions aim to discourage foreign countries and companies — over whom the US has no legal authority — from engaging with them.

- These measures act as “anti-circumvention tools”, forcing other nations to comply indirectly by threatening penalties.

- Because they apply outside US borders, secondary sanctions are often seen as extraterritorial and questionable under international law.

Why Countries Fear US Secondary Sanctions?

- The US dollar’s dominance in global trade and the central role of the American financial system make US sanctions highly influential worldwide.

- Any company or country engaged in international trade needs access to US markets and banks — losing that access can cripple business.

- Secondary sanctions don’t always impose fines; instead, they block foreign entities from the US financial system if they act against Washington’s foreign policy interests.

- Because of this, India’s refiners and banks are expected to cut back on Russian oil imports, fearing penalties.

- The US Treasury’s warning that secondary sanctions could hit buyers of Russian crude has already had an impact — experts predict an immediate drop in India’s Russian oil imports, which currently account for over 35% of total imports.

Why US Sanctions Matter for India?

- US sanctions carry real weight because they make banks, insurers, and investors cautious, cutting off access to funding and financial systems.

- Most Indian refiners — including Reliance Industries (RIL) and public sector companies — rely heavily on the US market, banking network, and technology partners. Losing that access would seriously impact their global operations.

- India’s Heavy Exposure to the US

- RIL, which buys nearly half of India’s Russian oil, has subsidiaries, partnerships, and investments in the US with firms like Google, Meta, and Intel.

- Public sector refiners also depend on dollar-based payments and the American banking system to buy crude oil, pay shippers, and insurers.

- Any disruption in US dollar transactions could severely hurt India’s refining sector.

- Impact on Russian Oil Imports

- To avoid secondary sanctions, Indian refiners and banks are expected to act with extreme caution, likely leading to a sharp drop in Russian oil imports.

- Government-owned refiners are already reviewing compliance risks, and RIL has said it will fully follow government guidance.

- Some refiners may try to buy Russian oil through third-party traders not directly targeted by sanctions.

- However, experts warn this loophole may not last, as the US could extend sanctions to these intermediaries if it wants to curb Russian oil flows more effectively.

- India’s Official Stand

- The Indian government has reiterated that it will buy oil from wherever it gets the best price, as long as the oil itself is not under sanctions.

- However, the new US restrictions on Rosneft and Lukoil — which supply over two-thirds of India’s Russian oil — could seriously limit India’s access to cheap Russian crude in the near term.

Oct. 30, 2025

Mains Article

30 Oct 2025

Why in News?

- India’s financial landscape is undergoing a major transformation as global giants — from Emirates NBD, Blackstone, Zurich Insurance, SMBC, Abu Dhabi’s IHC to Bain Capital — are acquiring significant stakes in Indian banks, insurers, and NBFCs.

- This marks a new phase of foreign capital infusion into a sector once considered over-regulated and closed, highlighting a strategic shift amid capital liberalisation.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Evolution of India’s Financial Sector

- Recent Big-Ticket Investments

- Why Global Giants Are Investing

- Regulatory Approach and Market Valuation

- Post-Crisis Sector Cleanup

- Opportunities and Strategic Advantages

- Risks and Concerns

- Way Forward

- Conclusion

Evolution of India’s Financial Sector:

- From protectionism to liberalisation:

- Historically, India’s financial sector was tightly regulated with limited foreign participation.

- Gradual policy reforms by the RBI and the government have allowed greater foreign ownership -

- Up to 100% in insurance companies.

- Up to 74% in private banks (with approval).

- Examples:

- Fairfax (Canada) was given special approval to hold a majority stake in CSB Bank for five years — a deviation from the 40% foreign cap, considering it a strategic revival investment.

- Foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) hold 48.39% stake in HDFC Bank, the second largest bank in the country.

Recent Big-Ticket Investments:

- Blackstone Inc, the world’s largest alternative asset manager, has acquired a minority stake of 9.99% in Federal Bank Ltd for Rs 6,196 crore.

- Bain Capital will be investing Rs 4,385 crore to acquire an 18.0% stake on a fully diluted basis via preferential allotment of equity and warrants in Manappuram Finance.

- Dubai-based Emirates NBD announced a $3 billion acquisition of a 60% stake in RBL Bank, making it one of the largest foreign takeovers in India’s financial sector.

- Japan’s SMBC acquired about 25% in Yes Bank, investing over $1.6 billion.

- Zurich Insurance bought a 70% majority stake in Kotak General Insurance for $670 million.

- Abu Dhabi’s International Holding Company also entered the fray with a nearly $1 billion investment in Sammaan Capital (formerly Indiabulls Housing), an NBFC.

- These deals mark the largest wave of foreign takeovers in India’s financial history.

Why Global Giants Are Investing?

- Robust growth fundamentals:

- India’s economy is growing at 6.8% (RBI estimate).

- The banking sector generated $46 billion net income (2024) with 31% YoY growth — higher than global average (McKinsey report).

- Credit growth is driven by small businesses, retail and housing sectors.

- Structural strengths:

- Low corporate leverage and focus on secured retail lending.

- India presents a vast, untapped and rapidly expanding financial market with over 400 million underbanked population, and a vast informal credit system.

- Digital infrastructure (UPI, Aadhaar, Jan Dhan) enables penetration and cost-efficient service delivery.

- Global context:

- Stagnation in developed markets (US, Europe).

- China’s tightening regulations and geopolitical risks have diverted capital toward India.

- India offers scale, political stability, demographic advantage, and credible regulation.

Regulatory Approach and Market Valuation:

- The RBI maintains a “positive but cautious” stance, ensuring fit-and-proper ownership and domestic control.

- Despite high performance, Indian banks remain undervalued — indicating market scepticism about long-term sustainability.

- The measured liberalisation of ownership ensures capital inflow while keeping regulatory sovereignty intact.

Post-Crisis Sector Cleanup:

- Past decade challenges: IL&FS and DHFL collapse, Yes Bank rescue, and NBFC liquidity crisis.

- Reforms implemented:

- Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) for resolution.

- RBI’s supervisory tightening and bad-loan cleanup.

- Result: Mid-sized banks and NBFCs have become stable and attractive acquisition targets.

Opportunities and Strategic Advantages:

- Global investors gain immediate access to licenses, branch networks, and customer bases — saving years of setup.

- For India, it brings foreign capital, innovation, and best practices in risk management and governance.

- Aids India’s march toward becoming a $7 trillion economy by early 2030.

Risks and Concerns:

- Financial sovereignty: Majority foreign ownership could shift strategic control offshore. Policy alignment during crises may not match domestic priorities.

- Exposure to global shocks:

- Rising global interest rates or liquidity tightening could lead to capital withdrawal, straining domestic credit flows.

- Lehman Brothers collapse (2008) serves as a reminder of global contagion risk.

- Competitive distortions: Foreign-owned entities may access cheaper global capital, disadvantaging domestic banks under tighter norms.

- Need for regulatory clarity: Larger and complex deals call for clearer frameworks on foreign control thresholds and compliance protocols.

Way Forward:

- Maintain calibrated liberalisation — attract capital while preserving regulatory autonomy.

- Develop a comprehensive framework for foreign ownership limits and voting rights.

- Strengthen macroprudential oversight to insulate from global volatility.

- Encourage domestic capital formation through sovereign and retail participation.

- Promote financial inclusion to reduce reliance on foreign investors in credit delivery.

Conclusion:

- India’s financial sector stands at a turning point — transitioning from protectionism to global integration.

- The surge in foreign investments underscores international confidence in India’s macroeconomic fundamentals, digital infrastructure, and regulatory credibility.

- However, balancing openness with sovereignty will define India’s success in becoming a $7-trillion, financially independent economy.

- The challenge for policymakers lies in ensuring that this capital inflow strengthens, rather than compromises, India’s financial stability and autonomy.

Mains Article

30 Oct 2025

Why in the News?

- China has filed a formal complaint against India at the World Trade Organisation (WTO), alleging that India’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes for batteries, automobiles, and electric vehicles violate global trade rules by favouring domestic products.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- India’s PLI Scheme (Background, Understanding PLI Scheme, China’s Allegations, WTO Rules on Subsidies, India’s Defence, Broader Implications, etc.)

China’s WTO Complaint Against India’s PLI Scheme

- China has formally filed a complaint with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) against India, alleging that several of India’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes violate global trade rules.

- Beijing claims that these schemes, aimed at promoting the manufacturing of advanced chemistry cell (ACC) batteries, automobiles, and electric vehicles (EVs), provide subsidies contingent on the use of domestic goods, thereby discriminating against imported products, including those from China.

- This dispute marks one of the most significant trade confrontations between India and China within the WTO framework in recent years, highlighting the broader tension between industrial policy ambitions and international trade rules.

Understanding the PLI Scheme

- Launched in 2020, India’s PLI scheme is a flagship initiative designed to strengthen domestic manufacturing, attract global investment, and integrate India into global value chains (GVCs).

- The scheme provides financial incentives to companies based on incremental sales of goods manufactured in India, aiming to make domestic industries globally competitive while fostering innovation and employment generation.

- The three PLI schemes challenged by China are:

- PLI for Advanced Chemistry Cell (ACC) Batteries: Encourages giga-scale battery manufacturing for EVs and energy storage systems.

- PLI for the Automobile and Auto Components Sector: Promotes the development of Advanced Automotive Technology (AAT) products, including EV components.

- PLI for the Electric Vehicle (EV) Ecosystem: Aims to attract major global EV manufacturers and reduce import dependence.

China’s Allegations Against India

- China’s central argument rests on the claim that these PLIs amount to prohibited subsidies under the WTO’s Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) Agreement.

- Beijing contends that:

- The PLI schemes are “Import Substitution (IS) subsidies”, as they encourage companies to use domestically produced goods over imported ones.

- For example, the PLI for the auto sector mandates a 50% Domestic Value Addition (DVA) requirement, while the ACC battery scheme stipulates a 25% DVA threshold for eligibility.

- These conditions, China argues, discriminate against foreign inputs and are inconsistent with WTO rules that prohibit subsidies contingent upon the use of domestic over imported goods.

- China maintains that such subsidies distort market competition and hinder its exports to India, particularly in sectors like EV batteries and automotive components, where Chinese manufacturers are global leaders.

WTO Rules on Subsidies and Trade Measures

- Under WTO law, countries have the sovereign right to provide subsidies for industrial development. However, the SCM Agreement ensures that such subsidies do not cause unfair trade distortions.

- Classification of Subsidies under WTO Law

- Prohibited Subsidies: Those contingent upon export performance or on the use of domestic goods over imported goods.

- Actionable Subsidies: Permitted subsidies that may still be challenged if they cause adverse effects on other WTO members.

- Non-Actionable Subsidies: Subsidies for legitimate public objectives such as R&D or environmental protection (currently lapsed).

- Import substitution (IS) subsidies fall under the prohibited category, as outlined in Article 3.1(b) of the SCM Agreement.

- Additionally, India’s PLI schemes may also be examined under:

- Article III.4 of GATT (National Treatment Principle): Prohibits countries from treating imported goods less favourably than domestic goods.

- Article 2.1 of the Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs) Agreement: Prohibits investment measures that are inconsistent with national treatment obligations, such as local content requirements.

- However, experts point out that India’s PLI schemes link incentives to value addition, not necessarily to the use of domestic goods.

- Value addition can occur through innovation, local assembly, or supply chain integration, making China’s claims legally complex and open to interpretation.

India’s Likely Defence

- Non-Contingency on Local Content: The Domestic Value Addition (DVA) benchmarks do not explicitly mandate the use of Indian goods; instead, they assess value creation within India, which can include imported components that undergo processing or transformation.

- Developmental Objective: The schemes are part of India’s broader industrial and climate strategy, promoting green mobility, battery storage, and self-reliance — areas considered essential for sustainable growth.

- Compliance with WTO Principles: India may argue that the subsidies are non-actionable, as they promote innovation, environmental sustainability, and technology diffusion — consistent with the WTO’s broader developmental objectives.

The WTO Dispute Process and Next Steps

- Under WTO rules, the first step in dispute resolution is consultations between the parties. India and China will attempt to resolve the issue through diplomatic discussions.

- If these consultations fail, the case will proceed to a WTO dispute panel for adjudication.

- However, the WTO’s Appellate Body, the final authority for appeals, has been non-functional since 2019 due to a U.S. veto on judge appointments.

- This means that even if the WTO panel issues a ruling against India and India appeals, the case will remain in legal limbo, allowing India to maintain its PLI policies until the appellate system is restored.

Broader Implications for India’s Industrial Policy

- The dispute highlights a broader tension between industrial policy and global trade rules.

- As countries increasingly adopt state-led incentives to promote manufacturing, especially in sectors like semiconductors, EVs, and clean energy, disputes of this nature are likely to rise.

- India’s PLIs are central to its “Make in India” and “Atmanirbhar Bharat” initiatives, aimed at reducing import dependence and building competitive domestic capabilities.

- Similar subsidy-driven strategies are being used by other economies, including the U.S. (CHIPS and Science Act) and the EU Green Industrial Plan.

- Therefore, this WTO case will test how global trade rules adapt to the new age of industrial competitiveness and green technology promotion.

Mains Article

30 Oct 2025

Context

- Ten years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement at COP21, the world faces a defining moment in its struggle against climate change.

- Despite the global pledge to keep warming well below 2°C and strive for 1.5°C, emissions and temperatures continue to rise at alarming rates.

- Floods, droughts, and heatwaves strike with increasing intensity, from Uttarakhand to Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir, reminding humanity that the climate crisis is no longer a distant threat but a lived reality.

- Yet, amid these challenges, the Paris framework has changed the world’s trajectory, demonstrating that collective determination and multilateral cooperation can alter the course of history.

From a 5°C Future to a 2°C Pathway

- Before 2015, the planet was heading toward a catastrophic 4°C–5°C of warming by the century’s end.

- Through global commitment and cooperation, that curve has been bent downward toward 2°C–3°C.

- This remains far from the safe zone identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), yet it represents undeniable progress.

- The shift proves that collective action works, and that multilateralism, though imperfect, remains essential.

- The Paris Agreement’s success lies in its fairness, flexibility, and solidarity, enabling countries with different capabilities to contribute according to their national circumstances while sharing responsibility for the global good.

A Decade After Paris Accord: Transforming the Global Economy

- The past decade has witnessed a turning point in global energy and economic systems. Ten years ago, fossil fuels were the cheapest and most competitive energy source.

- Today, renewables such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric power are leading new waves of growth and employment.

- This transformation marks a breakthrough for energy security, economic sovereignty, and environmental resilience.

- Equally remarkable is the rise of electric mobility. What once seemed an elusive dream has become a worldwide phenomenon.

- With electric vehicles accounting for nearly 20% of global new car sales, the transportation sector stands at the brink of a historic shift away from fossil fuels.

The Power of Partnership: The International Solar Alliance (ISA)

- Among the most inspiring achievements of the Paris decade stands the ISA, conceived at COP21 through the collaboration of India and France.

- What began as a visionary idea has evolved into a global coalition of over 120 countries, dedicated to making solar energy accessible to all.

- The ISA demonstrates how multilateralism can translate vision into action, fostering capacity building, financing mechanisms, and technological exchange.

- India’s leadership within this alliance reflects its growing stature in the global green transition.

- By securing 50% of its installed electricity capacity from non-fossil sources five years ahead of schedule, India shows that development and decarbonisation can advance together.

Priorities for the Next Decade

- First, global ambition must rise sharply. Despite improvements, current pledges remain insufficient.

- Nations must act decisively to reduce carbon emissions and preserve a liveable planet.

- Second, the global transition must be just and inclusive, protecting the most vulnerable communities.

- Investments in adaptation and resilience, through mechanisms such as the Green Climate Fund, the Loss and Damage Fund, and initiatives like CREWS—are vital to ensure that no nation or community is left behind.

- Third, the protection of natural carbon sinks, forests, mangroves, and oceans, must become a universal priority.

- These ecosystems, from the Amazon to the Sundarbans, are the planet’s best allies in absorbing carbon and safeguarding biodiversity.

- Fourth, non-state actors must be empowered. Local governments, scientists, businesses, and citizens play decisive roles in translating ambition into tangible outcomes.

- Their engagement transforms global commitments into visible, community-level results.

- Fifth, science must guide the transition. In an era clouded by misinformation, defending the integrity of the IPCC and promoting climate education are essential to ensure that facts, not fear, shape global decisions.

Conclusion

- A decade after Paris, the world’s climate journey stands at a crossroads between progress and peril.

- The achievements of the past ten years reveal a powerful truth: when nations unite under shared purpose, transformation follows.

- The Paris Agreement has redefined the global climate order, proving that multilateralism can deliver measurable change, that renewable energy can drive prosperity, and that adaptation and equity can coexist with ambition.

- The future remains uncertain, but the direction is clear. The world has chosen a path toward sustainability, and that path, however demanding, is unstoppable.

Mains Article

30 Oct 2025

Context

- The Constitution (One Hundred and Thirtieth Amendment) Bill marks a pivotal step in India’s effort to strengthen constitutional morality and political accountability.

- The Bill seeks to amend Articles 75, 164, and 239AA to mandate the removal of Ministers, including the Prime Minister and Chief Ministers, if they remain in custody for thirty consecutive days for an offence punishable with five years or more of imprisonment.

- While the proposal aims to uphold the integrity of public office, it has provoked widespread debate.

The Provisions of the Bill

- Under the Bill, a Minister’s arrest and detention for thirty consecutive days would compel the President or Governor to remove them from office on the advice of the Prime Minister or Chief Minister.

- If the Prime Minister or Chief Minister themselves are detained, they must resign or automatically cease to hold office.

- The measure seeks to prevent accused Ministers from retaining power, thus reinforcing public trust in governance.

- Yet, its reliance on arrest and custody duration as criteria for disqualification raises serious constitutional and procedural concerns, given the potential for abuse of discretionary powers by enforcement agencies.

The Discretionary Power of Arrest

- The power to arrest, under Section 41 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and its counterpart Section 35 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), is discretionary, not mandatory.

- Courts have consistently reaffirmed this position:

- In Joginder Kumar v. State of U.P. (1994), the Supreme Court held that no arrest should be made merely because it is lawful; it must be necessary and justified.

- In Deenan v. Jayalalitha (1989) and Amarawati and Anr. v. State of U.P. (2004), courts clarified that the term may arrest empowers but does not oblige the police to arrest, depending on the nature and context of the offence.

The Contentious Provisions: Detention, Bail, and the Problem of Thirty Days

- The Bail Dilemma

- The requirement that a Minister detained for thirty consecutive days must vacate office links political tenure to judicial timelines.

- Though the Supreme Court has repeatedly held that bail is the rule, jail is the exception, in practice, bail decisions are influenced by factors like the gravity of the offence and the judge’s stance on liberty under Article 21.

- This means a Minister could lose office before any judicial determination of guilt, contradicting the presumption of innocence. The thirty-day threshold therefore risks turning temporary detention into permanent political damage.

- Default Bail and Procedural Inconsistency

- The amendment also ignores default bail under Section 167(2) CrPC (or Section 187 BNSS), which grants bail if the investigation is not completed within 60 or 90 days.

- Since the thirty-day limit falls well within this period, a Minister might be removed from office before acquiring the right to bail, rendering the provision procedurally inconsistent and arbitrary.

- Special Statutes and Twin Conditions of Bail

- The Bill’s scope covers offences under any law in force, extending to stringent statutes such as the PMLA (Prevention of Money Laundering Act), NDPS Act, and UAPA (Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act).

- These impose twin conditions for bail, the accused must prove they are not guilty and unlikely to reoffend.

- Such provisions reverse the burden of proof, making bail within thirty days nearly impossible.

- The Manish Sisodia case, where bail was granted only after 17 months under the PMLA, exemplifies this difficulty.

- Consequently, the thirty-day benchmark could cause premature disqualification even before due judicial process concludes.

Political Implications and the Risk of Misuse

- Arrest as a Political Tool

- By linking ministerial survival to arrest and custody, the Bill risks converting the criminal process into a political instrument.

- In a context where investigative agencies are often accused of bias, such provisions may facilitate targeted arrests against political rivals.

- This undermines the principle of separation of powers and constitutional morality, replacing accountability with political expediency.

- What is designed to enhance integrity could instead erode democratic fairness.

- The Minister’s Dilemma

- The Bill also places Ministers in a Hobson’s choice:

- Either resign to secure bail, thereby surrendering office pre-emptively, or

- Stay in custody and face automatic removal.

- This dilemma creates administrative instability and penalises mere accusation, rather than proven guilt.

- It risks reducing executive authority to the outcome of legal tactics, not democratic mandate.

- The Bill also places Ministers in a Hobson’s choice:

Conclusion

- The Constitution (One Hundred and Thirtieth Amendment) Bill reflects a well-meaning yet flawed attempt to promote ethical governance.

- Ultimately, true ministerial accountability cannot depend solely on legal triggers. It must arise from political ethics, transparent governance, and a citizenry committed to democratic values.

- The Bill, in its current form, risks conflating political morality with punitive legality, thereby unsettling the delicate equilibrium between justice and politics in India’s constitutional framework.

Mains Article

30 Oct 2025

Why in news?

PM Modi addressed the Maritime Leaders Conclave and chaired the Global Maritime CEO Forum at India Maritime Week 2025 in Mumbai. He welcomed participants from over 85 countries, noting the event’s evolution from a national forum in 2016 to a global summit.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- India’s Maritime Strength and Economic Potential

- India Maritime Week 2025 – A Global Maritime Showcase

- PM Modi’s Address at India Maritime Week 2025: Key Highlights

India’s Maritime Strength and Economic Potential

- India’s 11,000 km-long coastline and 13 coastal states and Union Territories contribute nearly 60% of the national GDP.

- The nation’s 23.7 lakh sq km Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) attracts global investors, supporting 800 million residents in maritime regions.

- The 38 countries of the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) account for about 12% of global exports.

India Maritime Week 2025 – A Global Maritime Showcase

- India Maritime Week (IMW) 2025, held recently in Mumbai, is India’s premier global maritime event under the theme “Uniting Oceans, One Maritime Vision.”

- The event aims to showcase India’s roadmap to becoming a global maritime hub and a leader in the Blue Economy.

- This was the fourth edition of the summit. In 2016, the maiden India Maritime Week was held in Mumbai itself. Now, it has become a global summit.

- It served as a global convergence point for shipping, ports, shipbuilding, cruise tourism, and blue economy finance, driving collaboration for a sustainable maritime future.

PM Modi’s Address at India Maritime Week 2025: Key Highlights

- PM Modi addressed the Maritime Leaders Conclave and chaired the Global Maritime CEO Forum at India Maritime Week 2025 in Mumbai.

- During his address he highlighted India’s maritime transformation, global partnerships, and future ambitions for the blue economy.

- Several MoUs worth lakhs of crores were signed, reflecting global confidence in India’s maritime capabilities.

- India’s Vision for its Maritime Transformation

- India is committed to transform its maritime sector through the Maritime Amrit Kaal Vision 2047.

- This long-term vision rests on four strategic pillars:

- Port-led development

- Shipping and shipbuilding

- Seamless logistics

- Maritime skill-building

- The goal is to position India as a leading global maritime power.

- Major Achievements in India’s Maritime Sector (2024–25)

- Vizhinjam Port, India’s first deep-water international trans-shipment hub, became operational, hosting the world’s largest container vessel.

- Kandla Port launched India’s first megawatt-scale indigenous green hydrogen facility.

- JNPT doubled its capacity with the start of Phase 2 of the Bharat Mumbai Container Terminal, marking the largest FDI in India’s port infrastructure.

- India’s major ports handled record cargo volumes, showcasing unprecedented efficiency.

- Next-Generation Reforms in Maritime Governance

- Outdated colonial-era shipping laws replaced with modern legislation empowering State Maritime Boards, promoting digitization, and enhancing safety and sustainability.

- The new Merchant Shipping Act aligns Indian regulations with global conventions, improving trust, ease of business, and investment climate.

- The Coastal Shipping Act simplifies trade, ensures supply chain security, and promotes balanced coastal development.

- Introduction of One Nation, One Port Process to standardize port procedures and reduce documentation.

- Decade of Transformation under Maritime India Vision

- Over 150 new initiatives launched under the Maritime India Vision.

- Major ports’ capacity doubled, turnaround time reduced, and cruise tourism expanded.

- Inland waterway cargo movement rose by 700%, and operational waterways increased from 3 to 32.

- The net annual surplus of ports grew ninefold in ten years.

- Efficiency and Global Recognition

- Indian ports now rank among the most efficient in the developing world, outperforming many in the developed world.

- Container dwell time reduced to under 3 days, and vessel turnaround time cut from 96 to 48 hours.

- India improved its position in the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index.

- The number of Indian seafarers increased from 1.25 lakh to over 3 lakh, making India one of the top three seafaring nations globally.

- Focus on Blue Economy and Green Growth

- Emphasis on Blue Economy, sustainable coastal development, green logistics, and coastal industrial clusters.

- Government prioritizing shipbuilding as a national growth driver, with a ₹70,000 crore investment to boost shipyard capacity, greenfield/brownfield projects, and maritime employment.

- Large ships have been granted infrastructure asset status, enabling easier financing and reduced interest costs.

- Visionary Maritime Heritage and New Port Projects

- PM Modi recalled Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s maritime legacy, emphasizing that seas should be seen as gateways to opportunity.

- Announced construction of a new mega port at Vadhavan, Maharashtra, part of India’s effort to quadruple port capacity and increase containerized cargo share.

- Global Cooperation and Strategic Role of India

- India aims to strengthen global supply chain resilience and become a “steady lighthouse” amid global uncertainty.

- Highlighted India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor as a project redefining trade routes and promoting clean energy logistics.

- Reaffirmed India’s commitment to empowering Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries through technology, training, and infrastructure.

Mains Article

30 Oct 2025

Why in news?

Recently, the Supreme Court ruled that a person can reject a property sale made by their guardian after turning 18 if it was done without court approval.

The court said this can be done either by filing a case or through actions—for example, reselling the property—within the legal time limit.

The bench of Justices Pankaj Mithal and Prasanna B. Varale clarified that a formal lawsuit is not always necessary, reaffirming that a minor’s property rights can be protected by their clear conduct showing refusal of the sale.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Laws Governing Property of Minors

- Background of the Case

- Supreme Court on How Minors Can Reject Property Sales

Laws Governing Property Rights of Minors

- Property transactions involving minors are regulated by three key laws:

- The Indian Contract Act, 1872

- The Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956

- The Guardians and Wards Act, 1890

- Minors Cannot Enter into Contracts

- Under Section 11 of the Indian Contract Act, only adults of sound mind can enter into valid contracts.

- Any contract made by a minor is void from the beginning (void ab initio). This means it cannot be enforced by or against the minor.

- Exceptions:

- If the contract benefits the minor or provides necessities like food or education, the cost may be recovered from the minor’s property.

- A guardian can enter into a contract only if it benefits the minor.

- A minor cannot be a business partner but may receive profit shares under a valid agreement.

- Restrictions on Guardian’s Power to Sell Property

- Under Section 8 of the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956, a natural guardian can manage a minor’s property only for their benefit.

- The guardian cannot sell, mortgage, gift, or lease immovable property without court approval.

- If such a sale happens, Section 8(3) makes it “voidable at the instance of the minor”, meaning the minor can cancel it after turning 18.

- Similarly, Section 29 of the Guardians and Wards Act, 1890 also says a guardian needs court permission to dispose of a ward’s property.

- How a Minor Can Challenge the Sale After Majority?

- When a guardian sells property without permission, the law allows the now-adult person to challenge it.

- Traditionally, courts held that a formal case must be filed to cancel such a sale.

- However, in Abdul Rahman v. Sukhdayal Singh (1905), the court ruled that filing a suit is not always necessary — a clear act of repudiation, like reselling the property, is enough to show rejection.

- Time Limit for Challenging Such Sales

- According to the Limitation Act, 1963, the person has three years after turning 18 to challenge or reject a property sale made by their guardian without court approval.

Background of the Case

- The dispute involved two small plots (No. 56 and 57) in Davanagere, Karnataka, bought in 1971 by a father in the names of his three minor sons.

- Acting as their natural guardian, he later sold both plots without obtaining mandatory court approval.

- After turning 18, the sons resold both plots to another person, leading to two separate ownership disputes.

- What Happened in the Lower Courts?

- In the Plot 56 case, the High Court (2003) ruled that the sons’ resale amounted to a valid rejection of their father’s earlier sale. The ruling became final as it was not challenged.

- In the Plot 57 case, the buyer filed a case in 1997 claiming ownership.

- The trial court dismissed the suit, holding that the father’s sale was voidable and had been repudiated when the sons sold it after reaching adulthood.

- Appeals and High Court Ruling

- The first appellate court and the High Court later reversed the trial court’s decision, saying the sons’ later sale was invalid because they had not filed a formal case to cancel their father’s sale.

- The High Court declared the buyer as the rightful owner of Plot 57.

- Supreme Court Appeal

- This decision was challenged before the Supreme Court, which was asked to decide whether a person who was a minor at the time of sale must file a formal case to cancel the sale or can reject it by conduct after attaining majority.

Supreme Court on How Minors Can Reject Property Sales

- The Supreme Court clarified how a person can repudiate (reject) a property sale made by their guardian without court approval once they become an adult.

- The Court ruled that a minor, after turning 18, can reject such a sale in two ways:

- By filing a formal case (suit) to cancel the sale deed, or

- By clear conduct that shows they do not accept the earlier sale — for example, reselling the property or taking actions inconsistent with the guardian’s sale.

- The Court said that once the person rejects the sale, it becomes void from the beginning, and the buyer gains no rights over the property.

- Application in This Case

- The Court observed that the sons, after becoming adults, sold the same property within three years — the period allowed under law.

- Their names still appeared in the revenue records, and the earlier buyers had never taken possession.

- This conduct was enough to prove that the sons had repudiated their father’s sale, so no separate case was needed.

Oct. 29, 2025

Mains Article

29 Oct 2025

Why in news?

In recent weeks, the Indian diaspora has drawn global attention for religious and cultural displays that, in some cases, have crossed local norms in developed countries.

Incidents such as Ganapati idol immersion in public water bodies and Deepavali fireworks in residential areas have sparked controversy. In Edmonton, Canada, fireworks set two houses on fire, leading police to warn, “Light up your home, not your neighbour’s roof.”

Meanwhile, in Australia, anti-immigrant protesters have targeted Indians, while in the U.S. and Canada, nationalist groups have increasingly focused on the Indian community, reflecting a rising tension between cultural expression and local sensitivities abroad.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Diaspora Diplomacy and Soft Power

- Cultural Assertion and the Evolution of India’s Diaspora Policy

- India’s Approach to Overseas Citizenship

Diaspora Diplomacy and Soft Power

- India has become the world’s fourth-largest economy with a GDP of USD 4.19 trillion, supported significantly by its 35 million–strong diaspora.

- Comprising NRIs and OCIs, the diaspora contributes through remittances exceeding USD 100 billion annually, investments, and social initiatives like village development.

- From ancient traders and indentured labourers to today’s skilled professionals, Indian migration has evolved over centuries.

- Once criticized as a brain drain, it is now viewed as “brain gain,” symbolizing India’s global strength.

- India’s diaspora enhances soft power through culture, technology, and advocacy, influencing major outcomes like the U.S.–India nuclear deal.

- However, lobbying successes vary with host-country politics and diaspora unity.

Cultural Assertion and the Evolution of India’s Diaspora Policy

- A growing section of the Indian diaspora is displaying assertive cultural nationalism, promoting practices like Deepavali firecrackers abroad as symbols of community pride and identity.

- Simultaneously, some groups are urging the diaspora to advocate India’s political positions, especially in the United States.

- Historically, however, Jawaharlal Nehru maintained a clear distinction between India and its overseas communities.

- While the freedom movement had global links, Nehru insisted that post-Independence India stay out of PIO politics.

- He urged persons of Indian origin (PIOs) to remain loyal to their adopted countries, avoiding any perception of Indian interference in foreign domestic affairs.

- From Territorial to Cultural Nationalism

- In the early decades after Independence, India’s foreign policy and diaspora engagement were guided by territorial nationalism, not cultural identity.

- Issues like discrimination and racism were framed as universal human rights concerns, reflecting India’s commitment to global justice rather than ethnic solidarity.

- Rise of Global Cultural Nationalism

- From the 1990s onward, the increasing Indian migration created a global network of cultural nationalists.

- This trend gained strong momentum after Narendra Modi became Prime Minister in 2014, marked by large-scale diaspora rallies abroad, particularly in the United States.

- Growing Western Sensitivity to Foreign Influence

- At the same time, Western nations — notably the U.S., Canada, Australia, and parts of Europe — became increasingly wary of foreign interference in domestic politics.

- Allegations of Chinese and Russian influence sharpened this sensitivity, even as Israel’s lobbying began facing bipartisan criticism in the U.S.

- Although foreign influence operations are legal in the U.S. if transparently registered, the state-backed mobilisation of the Indian diaspora has drawn quiet scrutiny.

- India’s Position in the Changing Landscape

- Historically seen as a benign and diverse immigrant community, Indian Americans now face growing attention as India’s outreach to its diaspora becomes more overtly strategic.

- While India has avoided the hostility directed at Russia or China, there are increasing signs of Western unease over efforts to align diaspora networks with New Delhi’s political and cultural agenda.

India’s Approach to Overseas Citizenship

- India does not permit dual citizenship, but in 2003, it introduced Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) status through amendments to the Citizenship Act, 1955.

- This provided Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs) with lifetime visa-free entry, exemption from police registration, and rights similar to NRIs in education, property, and business.

- In 2015, the government merged the PIO and OCI categories, describing the arrangement as “dual citizenship in spirit, but not in law.”

- In contrast, the United States allows dual citizenship, but growing concerns about foreign political influence have prompted calls for stricter scrutiny.

- Analysts have voiced concerns about divided loyalties and potential foreign interference.

Navigating Nationalist Tensions Abroad

- As Western nations experience heightened nationalism, diaspora communities face pressure to demonstrate loyalty to host countries.

- For Indians abroad, expectations to promote India’s interests must be balanced with these realities.

- In an era of rising protectionism and political suspicion, “multi-alignment” diplomacy — being loyal to both India and the host nation — is increasingly difficult.

- Ultimately, nationalist fervour is not unique to India, and diaspora members must operate within the nationalist sensitivities of their adopted countries.

Mains Article

29 Oct 2025

Why in news?

Amid worsening air quality, the Delhi government, in collaboration with IIT-Kanpur, conducted two cloud-seeding trials to induce artificial rain, though only negligible rainfall was recorded — 0.1 mm in Noida and 0.2 mm in Greater Noida.

According to experts, the weak results were due to low cloud moisture (15–20% humidity), but more sorties are planned as better moisture conditions are expected in coming days.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Cloud Seeding

- Why Cloud-Seeding Trials in Delhi Failed to Induce Rain?

- How Cloud Seeding Helped Reduce Pollution?

- Conclusion

Cloud Seeding

- It is a weather modification technique used to enhance rainfall by introducing “seed” particles into suitable clouds.

- The method was first tested globally in the 1940s.

- The process involves dispersing cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) — particles that attract water vapour — or ice nuclei particles, which promote ice crystal formation.

- In natural conditions, water vapour condenses around airborne particles to form droplets that grow, collide, and eventually fall as rain.

- In cloud seeding, artificial nuclei such as silver iodide or salt particles are added to accelerate this process.

- Ice crystals grow faster, combine, and become heavy enough to precipitate, increasing the likelihood of rainfall.

- Process of Cloud Seeding

- To artificially induce rain, salts such as silver iodide, potassium iodide, or sodium chloride are used as “seeds” to create additional nuclei for cloud droplet formation.

- These particles are dispersed into clouds using aircraft, ground-based generators, rockets, drones, or flares.

- The method chosen depends on cloud type and conditions.

- Conditions Needed for Successful Cloud Seeding

- Cloud seeding can only be done when suitable clouds with adequate depth and moisture are present.

- As per the experts, cloud seeding needs humidity above 50%, cool temperatures, and existing cloud formation.

- The process requires a sufficient number of droplets inside clouds to enlarge through condensation and eventually fall as rain. It cannot be done under clear skies.

- In Delhi’s winters, cloud formation depends on western disturbances — weather systems originating from the Caspian or Mediterranean Sea that bring non-monsoonal rain to northwest India.

- However, these clouds often lack the required depth and liquid water content for effective seeding.

- Experts emphasize that before any attempt, it’s essential to assess cloud height, moisture levels, and liquid water content using specialized monitoring tools to determine if conditions are right for seeding.

- Environmental concerns

- Silver iodide (AgI), used in seeding, is insoluble but toxic in large quantities.

- Even small amounts (0.2 micrograms) can harm fish and microorganisms, though iodine in AgI is not considered toxic.

Why Cloud-Seeding Trials in Delhi Failed to Induce Rain?

- A Delhi government report cited low atmospheric moisture (10–15%), as predicted by the India Meteorological Department (IMD), as the main reason the cloud-seeding trials did not produce significant rainfall.

- Experts explained that although there was good cloud cover, moisture levels were too low to trigger rain.

- They added that the team gained technical experience from the trials and would conduct a third round once weather conditions improve.

- Limited Rainfall and Technical Challenges

- Experts noted that while Delhi plans more trials, cloud seeding in convective, low-level clouds remains highly uncertain.

- Success depends on timing, cloud type, altitude, and adequate moisture, conditions that are rarely met over the plains.

- Cloud bases were around 10,000 feet, which meteorologists said was too high for effective seeding.

- If clouds descend below 5,000 feet, chances of rainfall improve.

- The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) notes that the biggest challenge is quantifying seeding’s actual impact on precipitation.

How Cloud Seeding Helped Reduce Pollution?

- Despite limited rainfall — 0.1 mm in Noida and 0.2 mm in Greater Noida — the trials had a measurable impact on air quality.

- According to the Delhi government’s report, levels of particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) dropped after cloud seeding:

- PM2.5 fell from 221–230 to 203–207 across Mayur Vihar, Karol Bagh, and Burari.

- PM10 reduced from 206–209 to 163–177 in the same areas.

- The report concluded that while rainfall was minimal, pollution reduction was evident, offering valuable insights for future cloud-seeding efforts.

- Air Quality and Broader Solutions

- Air quality analysts cautioned that cloud seeding does not address emissions at their source.

- Experts point out that such measures — like smog towers or anti-smog guns — offer only short-term benefits.

- Sustainable improvement requires coordinated action across states, targeting emissions from transport, power plants, and construction, under an airshed-based approach.

Conclusion

Delhi’s cloud-seeding trials provided valuable learning but limited rain, highlighting the complex science, environmental risks, and logistical constraints of such interventions.

Experts agree that while cloud seeding can supplement pollution control efforts, lasting air quality improvement demands systemic emission reductions and regional cooperation.

Mains Article

29 Oct 2025

Why in the News?

- India’s services sector is in the news after NITI Aayog released two comprehensive reports highlighting that the sector now contributes 55% to India’s GVA and nearly 30% to total employment.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- India’s Service Sector (Background, Statistics, etc.)

- NITI Aayog Report on Service Sector (Key Highlights, Policy Priorities, etc.)

India’s Service Sector: Driving Jobs and Growth in a Transforming Economy

- India’s service sector has emerged as the core pillar of its economic transformation, shaping the country’s journey from an agrarian economy to a knowledge and innovation-driven one.

- Encompassing a wide range of industries, including information technology, financial services, communications, education, healthcare, transport, tourism, and retail, the sector not only drives GDP but also represents India’s global competitiveness.

- The sector’s contribution to India’s Gross Value Added (GVA) has steadily risen over the years, while its employment potential has expanded across both traditional and modern sub-sectors.

- India is today the 7th largest exporter of services in the world, with a share of over 4% in global services exports.

Key Highlights and Insights from the NITI Aayog Reports

- Employment Growth and Rising Share in Workforce

- According to the latest twin reports released by NITI Aayog, “India’s Services Sector: Insights from Employment Trends and State-Level Dynamics” and “India’s Services Sector: Insights from GVA Trends and State-Level Dynamics”, between 2017-18 and 2023-24, India’s service sector added nearly 40 million new jobs, raising its employment share from 26.9% in 2011-12 to 29.7% in 2023–24.

- This means almost one in three Indian workers is now engaged in the services economy.

- The report also notes an improvement in employment elasticity, which rose from 0.35 pre-pandemic to 0.63 post-pandemic, indicating that job creation is increasingly responding to output growth.

- The sector’s ability to absorb labour displaced from agriculture and low-productivity industry makes it a crucial driver of inclusive growth.

- Contribution to GDP and Economic Stability

- The services sector’s contribution to India’s Gross Value Added (GVA) increased from 49% in 2011-12 to 55% in 2023-24, outpacing the secondary and primary sectors.

- It also recorded a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of about 7%, showing consistent resilience even during economic downturns.

- Sub-sectors such as Information Technology (IT), financial and professional services, communication, and logistics have been the key growth engines.

- For instance, Computer and Information Services GVA increased nearly fourfold, from Rs. 2.4 trillion in 2011–12 to 10.8 trillion in 2023–24, highlighting India’s digital dominance and the rapid expansion of knowledge-based services.

- Traditional vs Modern Services

- While traditional services such as trade, repair, and transport continue to employ a large section of the population, modern services like IT, finance, R&D, and consulting have seen faster growth and higher productivity levels.

- The Professional, Scientific, and Business Services segment alone contributes about 20% of total services output, underlining the importance of high-skilled and innovation-driven activities.

- Conversely, postal, courier, and insurance services remain underperforming and require modernisation and digital transformation.

- Regional Trends and State-Level Dynamics

- The NITI Aayog’s state-level analysis reveals significant disparities in the development and composition of the services sector across India.

- Leaders: Karnataka, Maharashtra, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Delhi, and Kerala dominate the modern service economy, driven by IT, finance, and professional consulting. Together, they account for 40% of total services output.

- Lagging States: Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Odisha remain concentrated in low-value traditional services, with limited participation in high-value segments.

- Emerging Catch-Up: Encouragingly, lower-income states are showing “beta convergence”, meaning they are growing faster in services GVA, narrowing the regional gap over time.

- NITI Aayog recommends a “Build–Embed–Scale” framework to strengthen state-specific service ecosystems:

- Build - Invest in physical and digital infrastructure.

- Embed - Link services with industrial and skill ecosystems.

- Scale - Promote innovation and decentralised service delivery.

- Linkages with Income, Exports, and Digitalisation

- The correlation between a state’s service sector strength and its per capita income is strong; states with higher service contributions, like Karnataka and Telangana, record higher incomes.

- At the macro level, India’s services sector has become the largest recipient of FDI and a key contributor to foreign exchange earnings.

- India’s digitally deliverable services exports, such as software and IT-enabled services, have surged, supported by Global Capability Centres (GCCs) that employ over 1.6 million professionals.

- The report also highlights the growing importance of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), including UPI, DigiLocker, and e-governance systems, in enabling service delivery and financial inclusion across Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities.

Policy Priorities for the Road Ahead

- NITI Aayog stresses that service-led growth must be inclusive, sustainable, and regionally balanced.

- Key policy priorities include:

- Expanding digital and physical infrastructure across smaller cities.

- Establishing skill hubs for emerging areas such as fintech, AI, and healthcare.

- Promoting MSME integration into service supply chains.

- Strengthening data and institutional capacity for evidence-based policymaking.

- Encouraging green and sustainable services to align with India’s climate goals.

Mains Article

29 Oct 2025

Context:

- India’s goal of becoming a $30 trillion economy by 2047 and achieving net zero by 2070 places cities at the center of its development trajectory.

- Urban areas must evolve not just as centers of habitation but as engines of economic growth, sustainability, and resilience.

Urbanisation and the Developmental Imperative:

- Cities as growth engines: Most job creation and industrial expansion will occur in cities, and they are crucial for harnessing India’s demographic dividend.

- Climate commitments: Cities contribute significantly to GHG emissions and thus must lead in achieving net-zero and low-emission development.

- Vulnerability and resilience: High population densities make cities especially prone to disasters and pandemics, necessitating enhanced urban resilience.

Legacy of Urban Planning in India:

- Historical roots: India’s planning systems originated in the mid-1800s, primarily as a public health response to the plague.

- Current limitations:

- Focused narrowly on land-use planning rather than economic vision.

- Master Plans lack integration with long-term economic, climate, and resource goals.

- Growth projections are based on past population trends, not future job potential or economic expansion.

Need for an Economic Vision in Urban Planning:

- Economic vision first: Urban planning should begin with identifying key economic drivers for the next 20–50 years.

- Integrated framework:

- Assessments of population growth based on the number of jobs that are likely to be created.

- This will provide a basis for determining the infrastructure needs and land requirements for different purposes.

- In the absence of such an exercise, land-use plans lack a credible basis.

- Outcome: Transition from passive population-based planning to dynamic growth-based planning.

Natural Resource and Environmental Planning:

- Resource budgeting: Cities must conduct natural resource budgeting to assess carrying capacity and manage water, land, and energy sustainably.

- Demand management: Emphasis on efficient resource use and limiting urban expansion within ecological boundaries.

- Climate action plans: Every city should adopt a climate action roadmap for low-emission growth and resilience to extreme weather events.

Tackling Urban Pollution and Mobility Challenges:

- Air pollution crisis: Plans must include environmental management, especially for air quality improvement.

- Transport reforms: Development of Comprehensive Mobility Plans (CMPs) promoting -

- Public transport systems

- Non-motorised transport (NMT) like cycling and walking

- Reduced dependence on private vehicles

Regional and Tier-II City Integration:

- Beyond municipal boundaries: Urban economic planning should encompass peri-urban and regional linkages.

- Rural-urban synergy: Recognize economic interdependence between cities and surrounding rural areas.

- Smaller cities’ role: Affordable land and emerging industries make Tier-II and Tier-III cities vital for manufacturing and inclusive urbanisation.

Institutional and Educational Reforms Needed: